Mehdi Hasan

Link

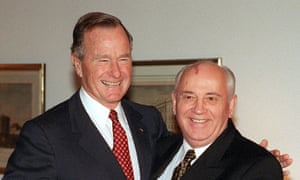

THE TRIBUTES TO former President George H.W. Bush, who died on Friday aged 94, have been pouring in from all sides of the political spectrum. He was a man “of the highest character,” said his eldest son and fellow former president, George W. Bush. “He loved America and served with character, class, and integrity,” tweeted former U.S. Attorney and #Resistance icon Preet Bharara. According to another former president, Barack Obama, Bush’s life was “a testament to the notion that public service is a noble, joyous calling. And he did tremendous good along the journey.” Apple boss Tim Cook said: “We have lost a great American.”

In the age of Donald Trump, it isn’t difficult for hagiographers of the late Bush Sr. to paint a picture of him as a great patriot and pragmatist; a president who governed with “class” and “integrity.” It is true that the former president refused to vote for Trump in 2016, calling him a “blowhard,” and that he eschewed the white nationalist, “alt-right,” conspiratorial politics that has come to define the modern Republican Party. He helped end the Cold War without, as Obama said, “firing a shot.” He spent his life serving his country — from the military to Congress to the United Nations to the CIA to the White House. And, by all accounts, he was also a beloved grandfather and great-grandfather to his 17 grandkids and eight great-grandkids.

Nevertheless, he was a public, not a private, figure — one of only 44 men to have ever served as president of the United States. We cannot, therefore, allow his actual record in office to be beautified in such a brazen way. “When a political leader dies, it is irresponsible in the extreme to demand that only praise be permitted but not criticisms,” as my colleague Glenn Greenwald has argued, because it leads to “false history and a propagandistic whitewashing of bad acts.” The inconvenient truth is that the presidency of George Herbert Walker Bush had far more in common with the recognizably belligerent, corrupt, and right-wing Republican figures who came after him — his son George W. and the current orange-faced incumbent — than much of the political and media classes might have you believe.

Consider:

He ran a racist election campaign. The name of Willie Horton should forever be associated with Bush’s 1988 presidential bid. Horton, who was serving a life sentence for murder in Massachusetts — where Bush’s Democratic opponent, Michael Dukakis, was governor — had fled a weekend furlough program and raped a Maryland woman. A notorious television ad called “Weekend Passes,” released by a political action committee with ties to the Bush campaign, made clear to viewers that Horton was black and his victim was white.

As Bush campaign director Lee Atwater bragged, “By the time we’re finished, they’re going to wonder whether Willie Horton is Dukakis’s running mate.” Bush himself was quick to dismiss accusations of racism as “absolutely ridiculous,” yet it was clear at the time — even to right-wing Republican operatives such as Roger Stone, now a close ally of Trump — that the ad had crossed a line. “You and George Bush will wear that to your grave,” Stone complained to Atwater. “It’s a racist ad. … You’re going to regret it.”

Stone was right about Atwater, who on his deathbed apologized for using Horton against Dukakis. But Bush never did.

He made a dishonest case for war. Thirteen years before George W. Bush liedabout weapons of mass destruction to justify his invasion and occupation of Iraq, his father made his own set of false claims to justify the aerial bombardment of that same country. The first Gulf War, as an investigation by journalist Joshua Keating concluded, “was sold on a mountain of war propaganda.”

For a start, Bush told the American public that Iraq had invaded Kuwait “without provocation or warning.” What he omitted to mention was that the U.S. ambassador to Iraq, April Glaspie, had given an effective green light to Saddam Hussein, telling him in July 1990, a week before his invasion, “[W]e have no opinion on the Arab-Arab conflicts, like your border disagreement with Kuwait.”

Then there is the fabrication of intelligence. Bush deployed U.S. troops to the Gulf in August 1990 and claimed that he was doing so in order “to assist the Saudi Arabian Government in the defense of its homeland.” As Scott Peterson wrote in the Christian Science Monitor in 2002, “Citing top-secret satellite images, Pentagon officials estimated … that up to 250,000 Iraqi troops and 1,500 tanks stood on the border, threatening the key U.S. oil supplier.”

Yet when reporter Jean Heller of the St. Petersburg Times acquired her own commercial satellite images of the Saudi border, she found no signs of Iraqi forces; only an empty desert. “It was a pretty serious fib,” Heller told Peterson, adding: “That [Iraqi buildup] was the whole justification for Bush sending troops in there, and it just didn’t exist.”

President George H. W. Bush talks with Secretary of State James Baker III and Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney during a meeting of the cabinet in the White House on Jan. 17, 1991 to discuss the Persian Gulf War.

Photo: Ron Edmonds/AP

He committed war crimes. Under Bush Sr., the U.S. dropped a whopping 88,500 tons of bombs on Iraq and Iraqi-occupied Kuwait, many of which resulted in horrific civilian casualties. In February 1991, for example, a U.S. airstrike on an air-raid shelter in the Amiriyah neighborhood of Baghdad killed at least 408 Iraqi civilians. According to Human Rights Watch, the Pentagon knew the Amiriyah facility had been used as a civil defense shelter during the Iran-Iraq war and yet had attacked without warning. It was, concluded HRW, “a serious violation of the laws of war.”

U.S. bombs also destroyed essential Iraqi civilian infrastructure — from electricity-generating and water-treatment facilities to food-processing plants and flour mills. This was no accident. As Barton Gellman of the Washington Post reported in June 1991: “Some targets, especially late in the war, were bombed primarily to create postwar leverage over Iraq, not to influence the course of the conflict itself. Planners now say their intent was to destroy or damage valuable facilities that Baghdad could not repair without foreign assistance. … Because of these goals, damage to civilian structures and interests, invariably described by briefers during the war as ‘collateral’ and unintended, was sometimes neither.”

Got that? The Bush administration deliberately targeted civilian infrastructure for “leverage” over Saddam Hussein. How is this not terrorism? As a Harvard public health team concluded in June 1991, less than four months after the end of the war, the destruction of Iraqi infrastructure had resulted in acute malnutrition and “epidemic” levels of cholera and typhoid.

By January 1992, Beth Osborne Daponte, a demographer with the U.S. Census Bureau, was estimating that Bush’s Gulf War had caused the deaths of 158,000 Iraqis, including 13,000 immediate civilian deaths and 70,000 deaths from the damage done to electricity and sewage treatment plants. Daponte’s numbers contradicted the Bush administration’s, and she was threatened by her superiors with dismissal for releasing “false information.” (Sound familiar?)

He refused to cooperate with a special counsel. The Iran-Contra affair, in which the United States traded missiles for Americans hostages in Iran, and used the proceeds of those arms sales to fund Contra rebels in Nicaragua, did much to undermine the presidency of Ronald Reagan. Yet his vice president’s involvement in that controversial affair has garnered far less attention. “The criminal investigation of Bush was regrettably incomplete,” wrote Special Counsel Lawrence Walsh, a former deputy attorney general in the Eisenhower administration, in his final report on the Iran-Contra affair in August 1993.

Why? Because Bush, who was “fully aware of the Iran arms sale,” according to the special counsel, failed to hand over a diary “containing contemporaneous notes relevant to Iran/contra” and refused to be interviewed in the later stages of the investigation. In the final days of his presidency, Bush even issued pardons to six defendants in the Iran-Contra affair, including former Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger — on the eve of Weinberger’s trial for perjury and obstruction of justice. “The Weinberger pardon,” Walsh pointedly noted, “marked the first time a president ever pardoned someone in whose trial he might have been called as a witness, because the president was knowledgeable of factual events underlying the case.” An angry Walsh accused Bush of “misconduct” and helping to complete “the Iran-contra cover-up.”

Sounds like a Trumpian case of obstruction of justice, doesn’t it?

A U.S. marshal, left, looking for a suspect, shows a mug shot to a man found allegedly using drugs in a crackhouse, according to police, in Washington, D.C., on July 18, 1989. The police raid was part of President George H.W. Bush’s war on drugs.

Photo: J. Scott Applewhite/AP

He escalated the racist war on drugs. In September 1989, in a televised addressto the nation from the Oval Office, Bush held up a bag of crack cocaine, which he said had been “seized a few days ago in a park across the street from the White House . … It could easily have been heroin or PCP.”

Yet a Washington Post investigation later that month revealed that federal agents had “lured” the drug dealer to Lafayette Park so that they could make an “undercover crack buy in a park better known for its location across Pennsylvania Avenue from the White House than for illegal drug activity” (the dealer didn’t know where the White House was and even asked the agents for directions). Bush cynically used this prop — the bag of crack — to call for a $1.5 billion increase in spending on the drug war, declaiming: “We need more prisons, more jails, more courts, more prosecutors.”

The result? “Millions of Americans were incarcerated, hundreds of billions of dollars wasted, and hundreds of thousands of human beings allowed to die of AIDS — all in the name of a ‘war on drugs’ that did nothing to reduce drug abuse,” pointed out Ethan Nadelmann, founder of the Drug Policy Alliance, in 2014. Bush, he argued, “put ideology and politics above science and health.” Today, even leading Republicans, such as Chris Christie and Rand Paul, agree that the war on drugs, ramped up by Bush during his four years in the White House, has been a dismal and racist failure.

He groped women. Since the start of the #MeToo movement, in late 2017, at least eight different women have come forward with claims that the former president groped them, in most cases while they were posing for photos with him. One of them, Roslyn Corrigan, told Time magazine that Bush had touched her inappropriately in 2003, when she was just 16. “I was a child,” she said. The former president was 79. Bush’s spokesperson offered this defense of his boss in October 2017: “At age 93, President Bush has been confined to a wheelchair for roughly five years, so his arm falls on the lower waist of people with whom he takes pictures.” Yet, as Time noted, “Bush was standing upright in 2003 when he met Corrigan.”

Facts matter. The 41st president of the United States was not the last Republican moderate or a throwback to an imagined age of conservative decency and civility; he engaged in race baiting, obstruction of justice, and war crimes. He had much more in common with the two Republican presidents who came after him than his current crop of fans would like us to believe.