Members of Shia group Asaib Ahl al-Haq carry the coffin of a fighter during a funeral in Najaf. The fighter was killed during clashes with the Free Syrian Army in Syria, according to the group. Photograph: Reuters

Each day for the past nine months, the bodies have been coming. Some are carried in simple wooden coffins strapped to car roofs. Others arrive with more ceremony, escorted by black-clad mourners or men in military fatigues to a hypnotic soundtrack of Islamic hymns.

The convoys turn into the lanes of the Valley of Peace cemetery, squeezing past tombstones weathered by millennia and stopping next to freshly dug holes in the desert soil.

The newest inhabitants of the world's biggest cemetery were killed not here in Iraq but in Syria, where they fought under the green flag of the Middle East's most potent new Shia Islamic political force, Asa'ib Ahl al-Haq (League of the Righteous).

The militia has been busy readying for the afterlife, buying up more than 2,500 square metres of burial plots and erecting shrines for its fallen. In Baghdad, nearly 100 miles north, the group has been more occupied with the here and now, imposing its influence on Iraq's fractured political scene and steadily asserting its will throughout the city's Shia heartland suburbs.

Since the US military left Iraq in December 2011, and within two months of the first national election since then, Asa'ib Ahl al-Haq has quietly emerged as one of the most powerful players in the country's political and public life. Through a mix of strategic diplomacy, aggressive military operations and intimidation – signature methods of its main patron, the Iranian general Qassem Suleimani – the group is increasingly calling the shots in two countries.

Qassem Suleimani, the Iranian general who is the main patron of Asa'ib Ahl al-Haq. Photograph: Handout

Qassem Suleimani, the Iranian general who is the main patron of Asa'ib Ahl al-Haq. Photograph: Handout

Its rise to prominence has disturbed many Iraqi political leaders. "Little more than seven years ago, they were just another Iranian proxy used to attack the Americans," said a minister. "Now they have political legitimacy and their tentacles in all the security apparatus. Some of us didn't notice until it was too late."

Until early 2007, few outsiders had heard of Asa'ib Ahl al-Haq, which emerged over several years from a split within the Mahdi Army, the then-dominant arm of the Shia insurgency in Iraq. Its earliest incarnation – stealth tactics and the denial of responsibilty for attacks – was straight from the playbook of Suleimani, an elusive Iranian general whose influence over Iran's strategic interests has grown sharply in the past 10 years.

The group has a close connection to Lebanon's Hezbollah and ideological links to Iran's supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Its debut as a strike weapon of Suleimani, who reports directly to Khamenei and commands the Quds Force of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards, came with an attack in January 2007 on a US military outpost in Karbala, another Shia shrine city, south of Najaf, that killed five US soldiers.

Several months later, the group's leader, Qais al-Khazali, his brother Laith al-Khazali and a senior Hezbollah member, Ali Moussa al-Daqduq, were captured by the SAS near Basra. Then came a series of events that gave rise to the group's claim to legitimacy.

In May 2007, a British IT consultant, Peter Moore, and four of his bodyguards were seized by Asa'ib Ahl al-Haq and Iraqi security force members from a government building in east Baghdad. Moore was released in late 2009 after the Khazali brothers were freed from US prisons in Iraq.

However, the Briton's guards were all killed, their bodies returned one by one as part of a choreographed exchange with Asa'ib Ahl al-Haq prisoners who were released from US and Iraqi prisons. Daqduq, one of the last to be freed, was returned to Lebanon in 2012.

The kidnapped Briton Peter Moore, shown in a video released in 2008 by his Iraqi abductors. Photograph: Reuters TV

The kidnapped Briton Peter Moore, shown in a video released in 2008 by his Iraqi abductors. Photograph: Reuters TV

Now, as Iraq approaches parliamentary elections on 30 April, the group is stepping up its political activism in Baghdad and its support for the regime of Bashar al-Assad in Syria. In speeches and interviews in the past two years, Qais al-Khazali has claimed a role for the group based on its military "defeat" of the US.

His message has galvanised thousands of Iraqi Shias who have volunteered to fight for the Assad regime in Syria. And it has worried many communities across the Shia heartland, who see their countrymen's involvement in Syria's battles as a costly investment in a sectarian conflict that increasingly respects no border.

In the Najaf cemetery, gravediggers say they can barely distinguish between the end of one war and the start of the next. "No sooner had the Americans gone than Syria exploded," said one worker, standing against a newly built shrine. "There have been more of their bodies coming back from Syria than ever before. There are easily around 500 of them buried here. We have been getting around three each day for the past month alone. They get driven to us from across the border in Iran. When they are killed in Syria, they are flown there."

The regular rhythms of life and death keep business ticking over in this graveyard of more than 5 million souls. But even by Najaf's standards, business has been brisk lately. A warm wind swirls soil from open graves nearby, and a newly etched tombstone spells out the short life of the Shia jihadist killed somewhere in Syria last November. His grave, and the 30-odd alongside it, all say the occupant died "defending the Holy Shrine Sayyidah Zaynab".

The mosque, on the south-west outskirts of Damascus, is said to be the resting place of the daughter of the Imam Ali, the prophet Muhammad's cousin, and is revered by the Shia faithful. Its defence has served as a clarion call for Shia fighters from around the Middle East who believe it to be under attack from Sunni extremists.

Hezbollah also claims its widespread intervention in Syria on the side of Assad is in defence of the shrine. So too does Kata'ib Hezbollah, another Iranian-backed Iraqi proxy, whose members are often buried alongside Asa'ib Ahl al-Haq fighters. Both Iraqi groups fight across Syria under the banner of Abu al-Fadl al-Abbas, which has been at the vanguard of attacks against the almost exclusively Sunni opposition across Syria.

They, along with the Iranian Revolutionary Guards, are helping turn the tide in favour of the Assad regime, which in late 2012 was losing control of Damascus to rebel groups who were finding serious cracks in the regime's inner cordon. "Then came a strategic decision by all the Shia groups to defend Assad whatever the cost," said a regional ambassador previously based in the Syrian capital. "You could see the turnaround in Assad almost immediately. Even in his speeches, it was like 'we can do this.'"

Estimates of the numbers of Shia fighters in Syria range between 8,000 and 15,000. Whatever the true figure, the involvement of large numbers of Iraqis is not the secret it was in the early months of Syria's civil war, which is now being fought along a sectarian faultline.

Outside Baghdad University, a large poster of Asa'ib Ahl al-Haq's dead, superimposed on a photo of the Sayyidah Zaynab shrine, greets students. Similar posters stand outside other universities, and on prominent public squares. Security forces pay them no heed.

"The government has given them cover for their political and security life," said a senior Iraqi official with links to the intelligence community. [The Iraqi prime minister Nouri] al-Maliki is wary of them, but what can he do? His nature is that if he cannot deal with the issue he will turn his head away. He tried to set up a cell to monitor them in late 2010, but they found out and he was embarrassed. He paid them money and said sorry. They don't respect him now."

Iraqi intelligence officials believe Asa'ib Ahl al-Haq is receiving $1.5m-$2m a month from Iran. "They see themselves as the 'Soldiers of the Marjaeen' [the ultimate Shia religious authority]," the official said. "Their power is unchecked."

The gravediggers who sit waiting for business in concrete huts along the main road through the cemetery fear nothing in death, but admit to being scared of the threat faced by anyone who earns the ire of Asa'ib Ahl al-Haq. "They are everywhere," said one. They're in the [official records] building. Don't go asking questions there. You will be arrested."

In Baghdad, homes and offices have been bought or, in some cases, commandeered by officials from the party who use them as recruiting centres for anyone looking to fight in Syria. Most locals seem to give them a wide berth.

"You need to be young and you need to have two written references," said a local man who had sat in on an interview between a would-be volunteer and Asa'ib Ahl al-Haq officials. "Those guarantees are important. It is also better if you don't have children, or a wife.

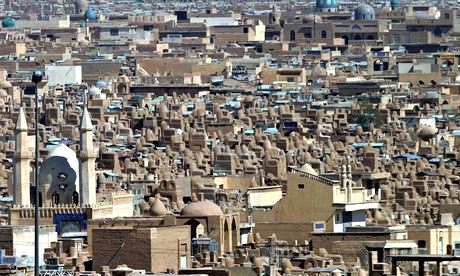

The vast cemetery in Najaf, Iraq, where 5 million bodies lie buried. Photograph: Akram Saleh/Reuters

The vast cemetery in Najaf, Iraq, where 5 million bodies lie buried. Photograph: Akram Saleh/Reuters

"If you are accepted, you will be taken to Iran for around two weeks for training and then you will be sent to Syria. It's the same way home if you die there. And if someone dies, they will be looked after by Iran. The families of martyrs are paid up to $5,000 each. And if they are too poor to pay for the burial, that will be taken care of too."

The Najaf gravediggers were staying ahead of the market, digging holes in advance for the bodies that would soon follow. Tombstones were piled nearby for up to 30 Keta'ib Hezbollah graves waiting for engravers. On a corner, a woman in a burqa was cleaning dust from large plastic bottles of pink rosewater that family members use to wipe tombs, new and old. A faint floral smell wafted on a dusk wind past the new arrivals. "We'll be back here tomorrow," said the gravedigger. "We will bury whatever they send us."

No comments:

Post a Comment