The Intercept

Link

A PLAN FOR the United Arab Emirates to wage financial war against its Gulf rival Qatar was found in the task folder of an email account belonging to UAE Ambassador to the United States Yousef al-Otaiba and subsequently obtained by The Intercept.

The economic warfare involved an attack on Qatar’s currency using bond and derivatives manipulation. The plan, laid out in a slide deck provided to The Intercept through the group Global Leaks, was aimed at tanking Qatar’s economy, according to documents drawn up by a bank outlining the strategy.

The outline, prepared by Banque Havilland, a private Luxembourg-based bank owned by the family of controversial British financier David Rowland, laid out a scheme to drive down the value of Qatar’s bonds and increase the cost of insuring them, with the ultimate goal of creating a currency crisis that would drain the country’s cash reserves.

Rowland has long had close relationships with UAE leadership, particularly with Abu Dhabi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed, known as MBZ. The bank is currently in the process of creating a new financial institution in cooperation with the UAE’s sovereign wealth fund, Mubadala, according to contracts and correspondence obtained by The Intercept outlining the terms of the deal. That project is separate from the Qatar operation, but it reflects the close relationship between the bank and the UAE.

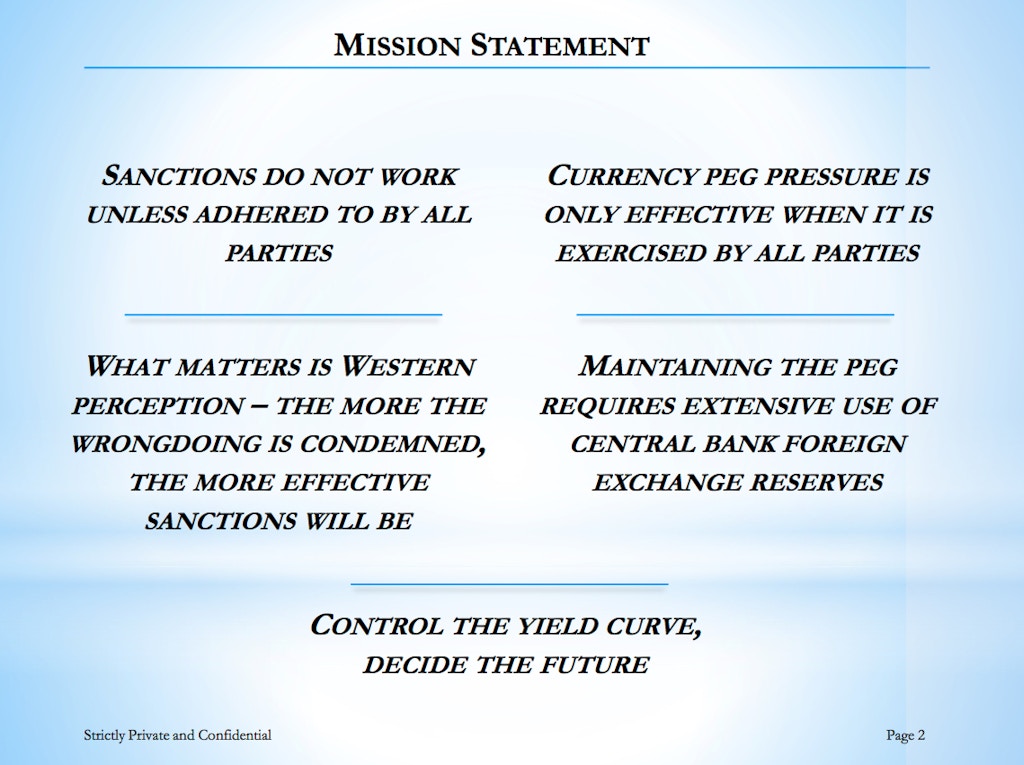

The Qatar debt project would be grandiose in its ambitions. “Control the yield curve, decide the future,” reads the planning document, referring to a standard financial-industry graph showing a country’s borrowing costs for debt that is due at different dates. The height and shape of the yield curve is thought to be a reflection of how healthy an economy is and influences what financing options are available to a country.

Targeting a nation’s economy using financial manipulation would be a dramatic break from traditional norms of diplomacy and even warfare.

The plan the document presents is far-fetched and appeared to have been put together by someone with little or no experience trading in credit and currency markets, two industry veterans who reviewed the plan for The Intercept said. Both were granted anonymity because speaking to the press could jeopardize their employment. “I can’t believe they put this on paper,” one of the credit veterans added. “They are talking about colluding to manipulate markets.”

There is no conclusive evidence the plan has been initiated, nor that it will ever be launched — and the current pressure Qatar’s currency is under as a result of an ongoing blockade imposed by the UAE means those direct, overt steps may be more effective economic sabotage than anything the slides outline. Additionally, the publication of this story means the secrecy the plan says it requires no longer exists.

The Intercept reached Edmund Rowland, David’s son and CEO of the U.K. branch of Banque Havilland, at a mobile phone number listed in internal company documents obtained by The Intercept and asked about the status of the plan to short Qatar on behalf of the UAE, referencing the document. “We’ve never done anything,” Rowland said. Asked for more details, Rowland responded, “I can’t make any comment,” and hung up.

After the call with Rowland, Herbert Kozlov, a lawyer with the firm Reed Smith, reached out to The Intercept and said on behalf of the bank that it had not traded in Qatari bonds or credit default swaps, the financial products the plan proposed to use. “Banque Havilland does not trade in bonds, securities, CDS, or any other instruments of Qatar and it has no plans to do so,” Kozlov said, reading a statement. As for the plan to take down Qatar, he said, “The bank is a prestigious private banking group and will not be drawn into or make comments on what are political storylines.”

The metadata of the slide deck obtained by The Intercept indicates Vladimir Bolelyy, an analyst with Banque Havilland, as the creator. A call by The Intercept to Bolelyy’s receptionist was rebuffed. “He’s been told by Herb Kozlov not to contact this company,” said the receptionist, referring to The Intercept. The Intercept had not previously told Kozlov that Bolelyy was listed as the author of the document.

THE NEW PROJECT comes amid — and, if implemented, would escalate — a regional crisis that reached new heights in June, when the UAE and Saudi Arabia led a bloc of Gulf nations in blockading and cutting off diplomatic relations with Qatar. U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson recently faulted the blockading countries for intransigence, but President Donald Trump has largely taken the opposite approach, emboldening Saudi Arabia and the Emirates at the expense of Qatar, which is home to one of the largest overseas U.S. military bases in the world. Tillerson traveled to the region on October 20 in the latest effort to defuse the crisis.

According to a report in the American Conservative, Tillerson previously told people close to him that he believed Trump had undermined him at the behest of Otaiba, the UAE ambassador, working through Trump’s son-in-law and White House adviser Jared Kushner, to whom Otaiba is close.

Both Kushner and Trump have reason to take sides with Otaiba in the dispute. The president has a Trump-branded golf course in Dubai and bragged at a press conference before his inauguration about a deal he was offered by a billionaire Emirati real estate developer.

The president’s attempts to get his hands on Qatari money have been less successful. In 2010, Trump traveled to Qatar with his daughter Ivanka Trump in an attempt to secure two different sources of investment funding. He was unceremoniously rebuffed by both.

More recently, Kushner sought a $500 million bailout from a Qatari royal as part of a plan to redevelop his badly underwater flagship investment in a New York office tower. The money for such bailouts often comes from the Gulf. As The Intercept first reported, the Qatari royal agreed to help bail out the Kushners, contingent on their ability to raise the rest of the funding they needed from other sources. The remainder of the funding, however, fell through, and the Qatari royal pulled out of the deal.

After the deal fell apart, Kushner helped orchestrate an unyielding response to the Saudi- and UAE-led economic blockade of Qatar, which Trump took credit for sparking with a hardline approach at a summit in Riyadh. Former top White House adviser Steve Bannon also credited Trump with stoking the blockade at a recent event in Washington. “I don’t think it’s just by happenstance that two weeks after that summit, that you saw the blockade by the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Egypt, and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia on Qatar,” Bannon said at a think tank. “And I’ve said from day one, even with the situation in the Pacific, with northwest Korea, I think the single most important situation in the world, that’s happening right now, is the situation in Qatar.”

In late June, Trump waded further into the conflict with remarks aimed at Qatar during a private fundraiser, according to audio obtained by The Intercept. “We’re having a dispute with Qatar — we’re supposed to say Qatar,” Trump said, mocking the pronunciation of the country’s name by varying the syllabic emphasis. “It’s Qatar, they prefer. I prefer that they don’t fund terrorism.”

Regional tensions ratcheted up another few notches over the weekend, as Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, a close ally of both Otaiba and MBZ, arrested dozens of princes and other top officials in a swift consolidation of power and followed it up with a threat to wage war against Iran.

THE ECONOMIC BLOCKADE has already directly impacted Qatar’s economy, decimating trade, travel, and finance flows in and out of the country. Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund recently brought $20 billion back to the country to prop up the country’s banking system, and the country’s currency is already showing signs of financial stress.

The cost of insuring Qatari debt has risen some 70 percent since May, the stock market is down 24 percent this year, and yields are rising ahead of a bond offering to be made by the end of the year. Ahead of that debt sale, the country abruptly changed how it calculates how much foreign currency reserves it has, a key metric investors use to assess how risky it is to buy a country’s debt. The move doubled Qatar’s foreign currency reserves and came as a complete surprise to international officials, who normally discuss and review foreign reserve accounting before they are publicly announced. Instead, in this case, Qatar simply released a six-word statement changing its accounting. Despite the unexpected move, the Wall Street Journal noted that “Qatari bond yields are still relatively low for an emerging-market country, reflecting the country’s vast oil reserves and attendant wealth.”

Banque Havilland is best known for its role in a previous incarnation in the bankruptcy of Iceland, from which it sprung as a new bank out of the Luxembourg branch of the Icelandic bank Kaupthing, and for a willingness to work with controversial clients, such as Nigerian tycoon Kola Aluko.

David Rowland launched Banque Havilland with the help of his friend Prince Andrew. Rowland has been an active ally of the conservative British Tory Party and is said to be close to David Cameron, the former British prime minister. Rowland was said to have paid £20,000 — about $23,000 — for a portrait of Cameron at a Conservative Party fundraiser and was briefly named treasurer of the Tories in 2010, before withdrawing amid controversy.

The bank is named after the Rowland’s family home on the tax-haven island of Guernsey, Havilland Hall. Though Edmund Rowland runs the bank, internal documents show his father David remains involved. Documents marked “secret and confidential” outlining the plan for the financial attack against Qatar were being circulated between Banque Havilland and the Emirati embassy in Washington as recently as late September.

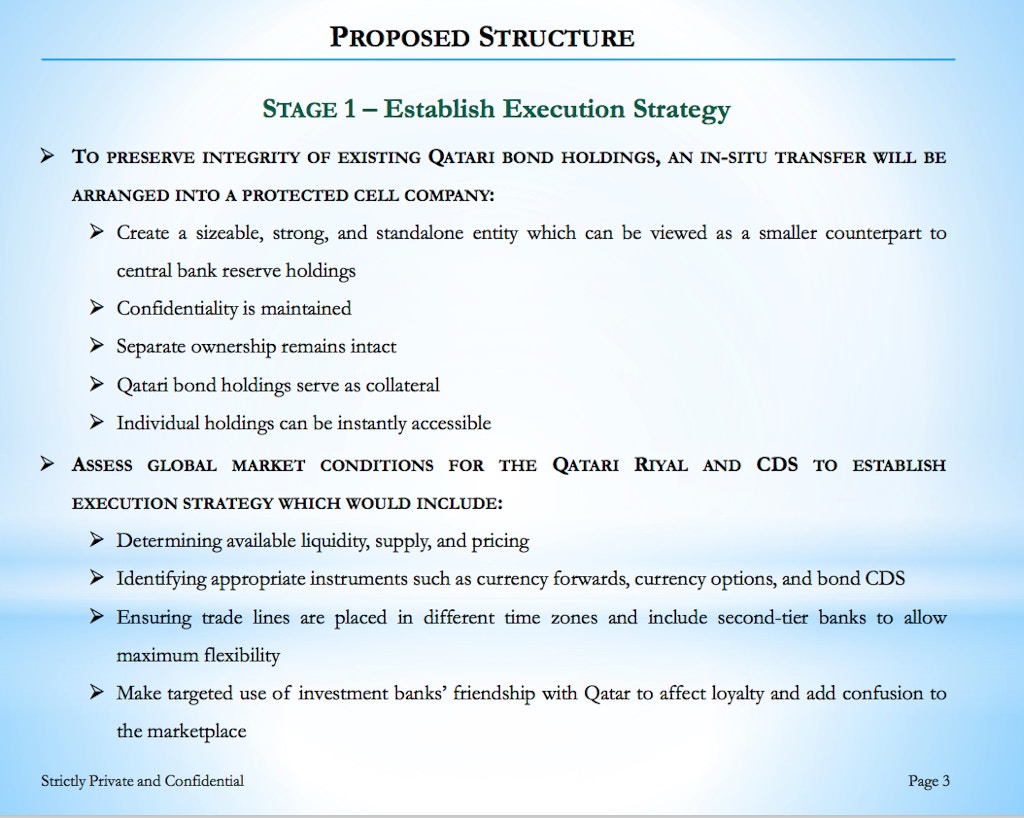

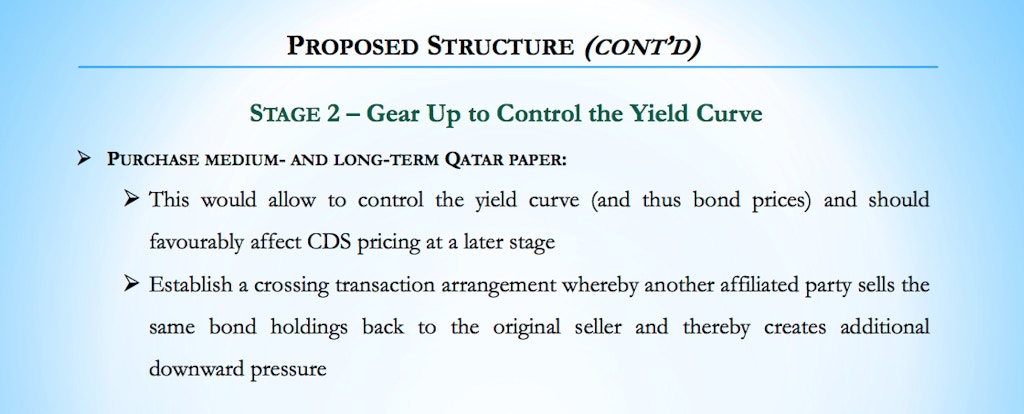

A PRIVATE FINANCIAL institution like Banque Havilland would be very familiar with the first step of the plan as laid out in the outline: creating a new offshore investment fund constructed to obscure its links to the UAE. The fund would hold Qatari bonds already owned by the UAE, as well as additional debt the fund could buy. The fund would also buy credit default swaps, which would rise in value as Qatari debt sank.

The plan then calls for precipitating a run on the debt through a series of sham transactions to drive down the price of Qatar’s bonds – a manipulation technique known as “painting the tape,” where players swap instruments back and forth to create the false appearance of a high volume of trades. The hope is to get other traders who aren’t in on the plan to see the high volume on the “tape” — the market ticker — and think that, since volume is high in a period of political turmoil, something important must be happening, prompting them to sell. The sales, if the technique goes to plan, would drive the price of the bonds down, creating more panic and more selling. According to the plan, the UAE, having bought credit default swaps against the debt, would see the value of that insurance rise as Qatari debt tanked.

The document outlining the scheme puts the bond trading proposal in print: “Establish a crossing transaction arrangement whereby another affiliated party sells the same bond holdings back to the original seller and thereby creates additional downward pressure.”

The hope is to spark a run by bond investors who think everybody else is selling, so they better get out quickly.

Falling debt prices and rising costs of the default swaps would signal a fresh crisis to the markets, putting pressure on Qatar’s currency. The Qatari riyal is pegged to the U.S. dollar, so as its offshore value falls, the country would be forced to spend billions of dollars from its reserves to push it up.

In other words, the UAE plans to short Qatar, then drive it into the ground by manipulating international financial markets, all while gaining diplomatic leverage against its rival.

Speculating about a country’s currency and economic future is far from unprecedented in the high-flying world of finance, but the difference in this case is that the plan is not designed for a vulture fund bent on a profit, but a sovereign state looking to undermine a neighboring nation.

The plan is not an obvious winner from a profit perspective, which further suggests its goals to be political rather than financial. As the document notes, at the end of the operation — if it’s successful — it will be difficult for the UAE to unload its Qatari bonds because the attack would have largely weakened Qatar financially.

And that’s if the plan even works. “It is very difficult to manipulate a sovereign [country’s] yield curve,” Frank Partnoy, a finance and law professor at the University of San Diego who formerly structured derivatives at Morgan Stanley, told The Intercept. “This belongs in a James Bond movie but probably wouldn’t work very well in practice.”

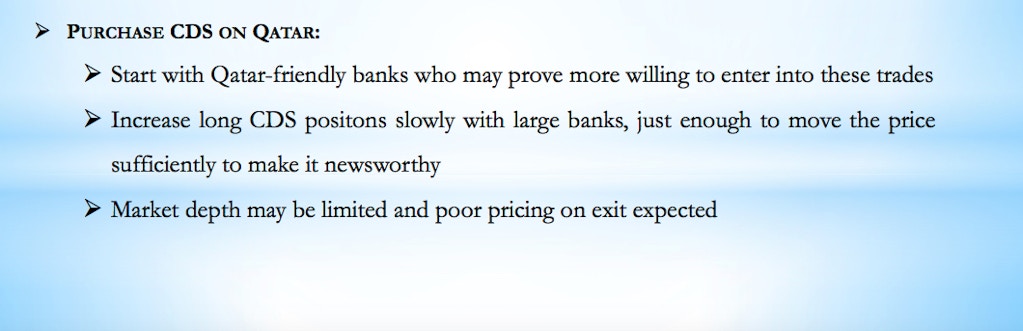

A screenshot of the plan dealing with the purchase of credit default swaps on Qatari debt. The CDS instruments rise in value as the bonds fall, allowing the UAE to profit from the collapse of Qatar’s currency.

Photo:Global Leaks

RATHER THAN OUTLINE specifics, the document speaks in a vague, somewhat harebrained tone: It doesn’t contain any analysis of Qatari bond, derivative, or currency markets or an estimate of the total economic firepower the UAE can put behind the plan, nor does it address how much of Qatar’s $68 billion in outstanding debt the UAE and it allies already own; how to respond when, as is likely to happen relatively quickly in these lightly traded markets, the Qataris see strange trades and apply pressure to markets in the opposite direction by buying their bonds, stabilizing their currency, and selling credit default swaps; or whether a successful attack on a pegged currency in the region will whip back and lead to pressure on the UAE dirham, the Saudi riyal, and the pegged currencies of their allies.

The plan, instead, lays out a conceptual scheme in several phases, the first of which takes a close look at Qatari currency and credit markets to figure out “available liquidity, supply, and pricing.”

If all goes according to plan, the next move would be to force Qatar to blow through its cash to prop up its currency. “Maintaining the peg requires extensive use of central bank foreign exchange reserves,” reads the outline’s mission statement. The idea would be that as the Qatari bond market tanks, so will the country’s currency. And as holders of Qatar’s currency sell it off and exchange it for dollars, the country’s dollar reserves plummet.

The basic premise of the plan — that Qatar is spending billions of dollars to offset the pain inflicted by the blockade and that the country’s currency is vulnerable — is largely correct. Just before the blockade against Qatar was enacted, the sheikdom held at least $35 billion in currency reserves. After the embargo, Qatar’s reserves plummeted as it spent to prop up its currency and keep its economy afloat. The country now holds just under $24 billion in reserves, though a recent accounting maneuver roughly doubled that number.

Because the country is incredibly rich, Qatar’s official reserves understate how much money it has to defend its currency. The government can call on the vast liquid wealth of Qatar-based corporations, its $335 billion sovereign wealth fund, and its citizens to stabilize the currency or support the economy. For instance, the recent repatriation of $20 billion of the sovereign wealth fund’s cash from international accounts back to onshore banks effectively bailed out Qatar’s financial system, and some government funds are already selling assets.

Qatar may be spending tens of billions of dollars to fight the economic effects of the blockade, but it has hundreds of billions of dollars more. And, on the record, Qatar insists that it has sufficient reserves to keep its currency pegged to the dollar.

As a result, the plan would be anything but a sure bet, financially speaking.

Keeping the outline light on details makes sense, said Partnoy, the University of San Diego professor, in the context of the way banks generally operate. “Bankers are always trying to sell complicated products that will make them fee income,” he said. “This is an effort to try to sell something that might be a terrible idea.”

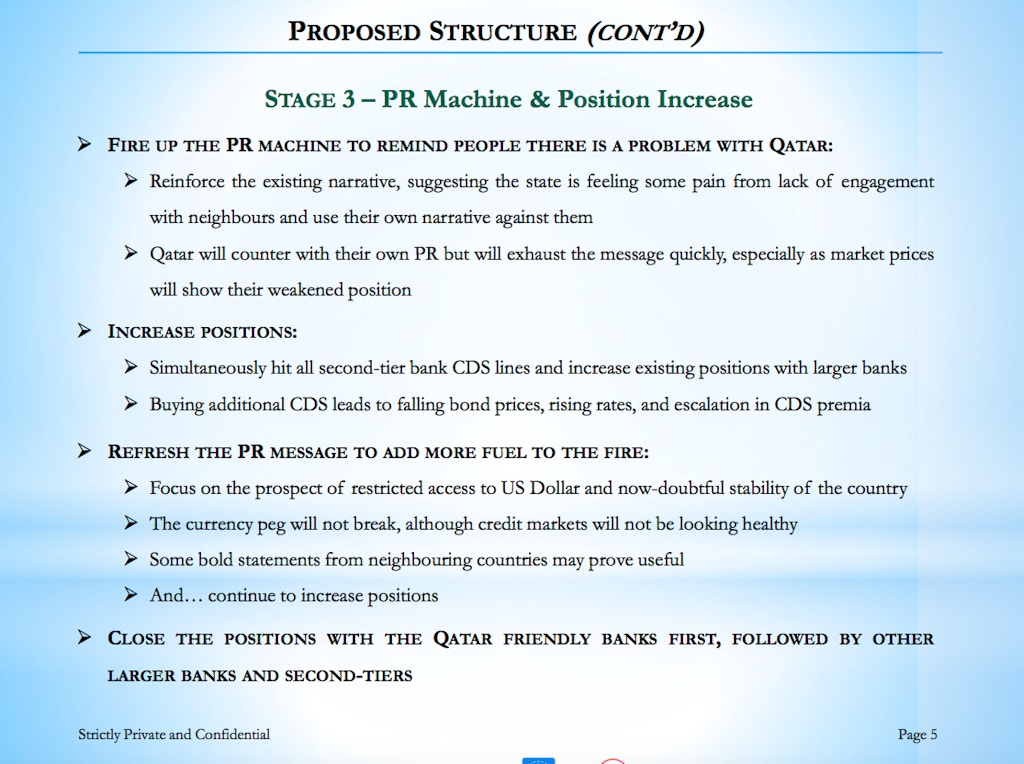

THE THIRD STAGE of the plan would be to ramp up the “PR machine” in order to slam Qatar internationally, pointing to its weakening financial situation. “Focus on the prospect of restricted access to US Dollar and now-doubtful stability of the country,” the plan reads. “And … continue to increase positions.” In other words, keep the market cornered and feed fears about falling prices with manufactured bad news.

The public relations effort also calls on other countries for help — presumably UAE allies, like Egypt and Saudi Arabia, which have in recent months teamed up with the Emirates to blockade Qatar. “Some bold statements from neighbouring countries may prove useful,” the plan says.

Jacob Frenkel, a former Securities and Exchange Commission enforcement lawyer and federal criminal prosecutor who has served as an expert witness in market manipulation cases, said the proposal raises serious red flags. Because the plan would likely involve trades in U.S. markets and would use U.S. servers and dollars, American regulators and prosecutors would have jurisdiction over it.

Frenkel, now a partner at the law firm Dickinson Wright, said that agreements about timing and pricing of trades are common in manipulation schemes. “The use of entities created for the purpose of engaging in transactions to create the perception of an independent market interest is a characteristic found in market manipulative activities,” he said. That alone is a “red flag that would be of interest to a regulator. And anybody in law enforcement would acknowledge what I’m saying.”

THE DOCUMENTS WERE provided to The Intercept by an opaque group that calls itself Global Leaks. Over the summer, Global Leaks began distributing emails from Otaiba’s inbox to media outlets, including The Intercept. Little is known about the organization, but the Global Leaks operatives use a .ru email account, which suggests they are either Russian or attempting to give that impression. Global Leaks claims it is not connected to the Russian government or any other government.

Global Leaks said it received the documents from sources connected to Banque Havilland, a claim The Intercept investigated and found had merit, though other possibilities — such as a hacking operation — can’t definitively be ruled out.

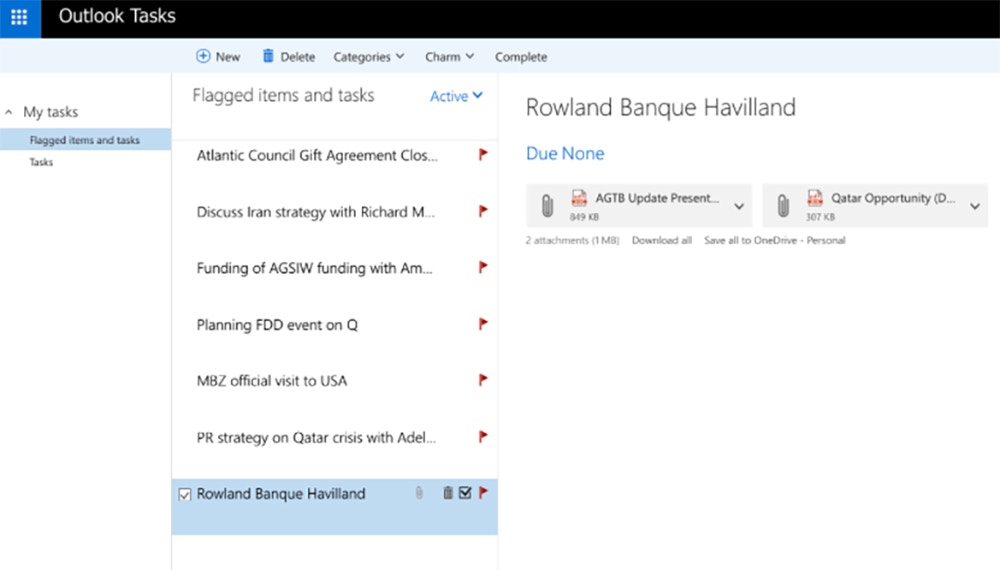

After obtaining the documents, Global Leaks operatives said they asked a source who maintains access to Otaiba’s inbox to search for documents related to Rowland or Banque Havilland. That source found the slide deck outlining the scheme in Otaiba’s Outlook tasks — a folder designed to serve as a “to-do” list — and provided it to Global Leaks.

Otaiba’s use of a Hotmail account for sensitive diplomatic business was itself questionable when it was reported compromised earlier this year — that he continues to do so months later is even more puzzling. Otaiba has not responded to emails from The Intercept, including one requesting comment for this article, but a Washington, D.C. journalist who corresponds with him recently shared an email sent by Otaiba from the same compromised account. Emails to Otaiba’s Hotmail account were not responded to but did not bounce back.

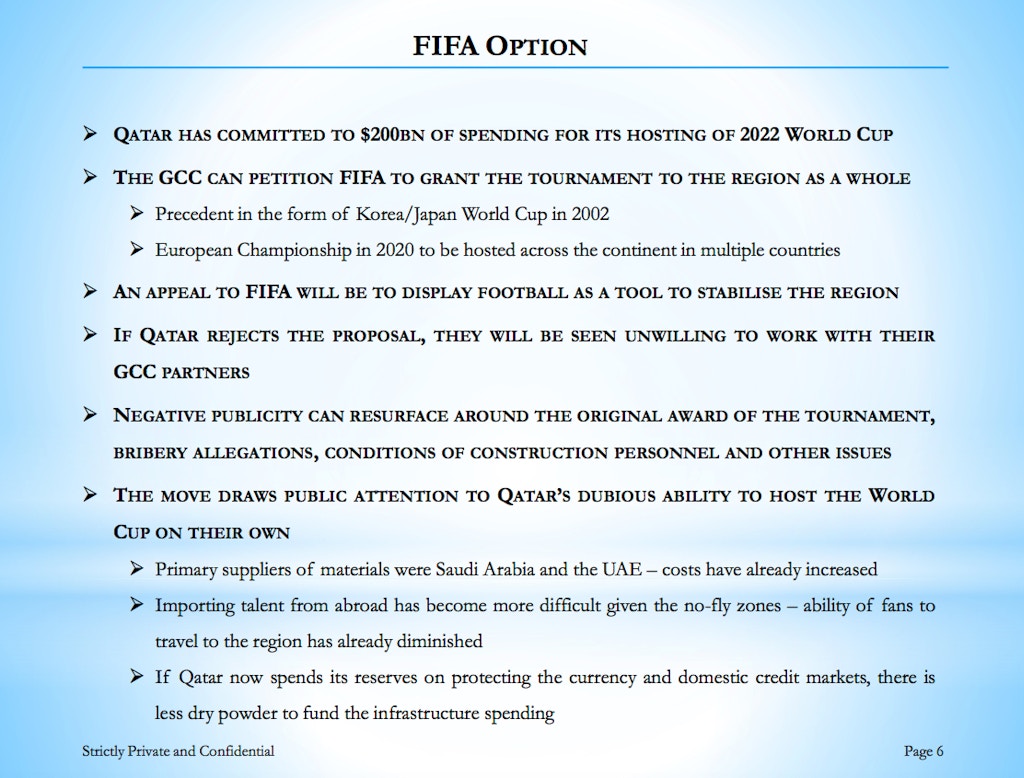

WHILE THE SCHEME itself would be an ambitious undertaking, the goal is ultimately petty: It’s about soccer.

One of the plan’s stated aims is forcing Qatar to share soccer’s 2022 World Cup, according to the outline. The strategy laid out in the document calls for using a public relations campaign to point the international soccer body FIFA to Qatar’s dwindling cash reserves, making a case that the small Persian Gulf monarchy can’t afford to build the necessary infrastructure.

The blockade is already raising prices for infrastructure supplies and recruiting top officials to work in Qatar has been difficult, the slides point out. The outline concludes with the hope that the economic war will make it harder for Qatar to continue building stadiums and other assets needed to host the games: “If Qatar now spends its reserves on protecting the currency and domestic credit markets, there is less dry powder to fund the infrastructure spending.”

The UAE, according to the document, hopes to make a push for the Gulf Cooperation Council — a group of Arab monarchies that includes Qatar — to host the premiere global sports event across the member nations, rather than in Qatar alone.

On October 20, several weeks after The Intercept first obtained the document outlining the plan, a well-funded Twitter campaign launched with the goal of taking the World Cup from Qatar, complete with a slickly produced video.

“An appeal to FIFA will be to display football as a tool to stabilise the region,” the document reads. “The GCC can petition FIFA to grant the tournament to the region as a whole.” If Qatar rejects the idea, the plan contends, “they will be seen unwilling to work with their GCC partners” — one of which would have just launched a surreptitious financial attack against the country.

No comments:

Post a Comment