The pressure slowly increases on Bashar Assad

The Economist

AFTER four and a half years that have ravaged the country and sucked in ever more combatants—the latest being Turkey—Syria’s ghastly civil war seems as intractable as ever. But like the twisting narrative of an endless television serial, its multiple subplots do give hints of inching to a conclusion. Not, most likely, in this current hot and bloody summer season, but perhaps in the not-too-distant future.

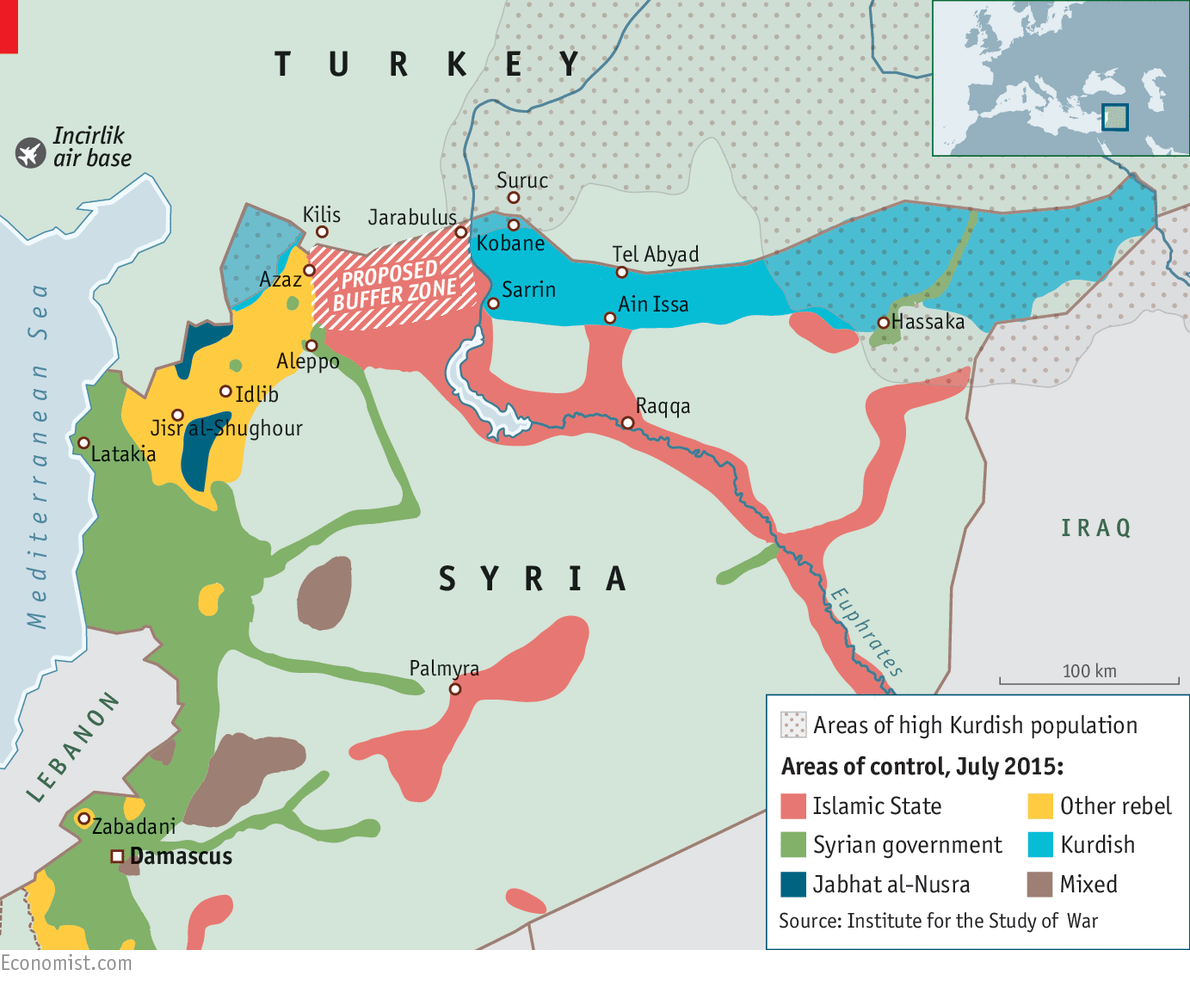

Until early this year two of Syria’s players, the regime of Bashar Assad and Islamic State (IS), were in the ascendant. The tide against both has since turned. Recent analysis by Jane’s, a defence analyst, suggests that after a series of losses to both IS and other, rival rebel groups, the area fully controlled by government forces has shrunk since January by some 16%, to a mere 30,000 square kilometres (11,600 square miles), or barely a sixth of Syria’s territory.

And this was before a recent offensive by a coalition of mostly Islamist militias calling itself Jaish al-Fatah, which on July 28th captured the government’s last salient on the route linking Syria’s second city, Aleppo, to the coast. The advance, which follows the fall in March of a provincial capital, Idlib, and of another big town, Jisr al-Shughour, in April, further consolidates rebel control of Idlib province. Jaish al-Fatah now threatens both the surrounding rich agricultural region and the coastal mountain range that is the heartland of Mr Assad’s own Alawite sect.

Analysts cite several reasons for the government’s setbacks. Foreign backers of Sunni rebel groups, including Saudi Arabia and Turkey, have increased the volume and quality of military supplies, helping redress a stark imbalance in firepower. Mr Assad’s own forces, depleted by attrition, desertion and a leakage from the formal army into informal pro-government local militias, no longer have the manpower and discipline to sustain multiple fronts. They rely increasingly on foreign Shia “volunteers”, including Iranian-trained Iraqi and Afghan fighters, and Lebanon’s Hizbullah. The latter has been bogged down in a long siege of the town of Zabadani, a rebel enclave on the border with Lebanon.

The government’s retrenchment may be partially deliberate. “Hizbullah and Iran had been asking Mr Assad to adopt a more realistic strategy, “ says Emile Hokayem of the International Institute for Strategic Studies. “He resisted admitting that he could not control all Syria’s corners, but realised that is untenable.” The Syrian president conceded as much in a recent speech. “We must define the important regions that the armed forces hold onto so it doesn’t allow the collapse of the rest,” he said. Having recently granted an amnesty to deserters in an effort to drum up recruits, Mr Assad also hinted that the government may order a general mobilisation, allowing it to commandeer vehicles, machinery and other civilian property.

Despite the fact that Turkey has long argued for a stronger international effort against Mr Assad, its formal entry into the fray is unlikely to tip the equation decisively against Syria’s regime. Iran, soon to be flush with funds unblocked by the lifting of sanctions, is for now at least still committed to propping up the Syrian leader. Even with better weapons and stronger momentum, Sunni rebels lack both the manpower and unity of command needed for a push towards Damascus, the Syrian capital. Some of their component groups, such as Jabhat al-Nusra, which declares allegiance to al-Qaeda, remain anathema to Western powers who might otherwise be keener to accelerate Mr Assad’s fall.

Despite its success at Palmyra, IS’s “caliphate” is an unhappy place, bludgeoned from the air by coalition strikes and shrinking in size. Kurdish forces have relentlessly expanded since breaking the jihadists’ siege of Kobane last winter, most recently seizing the town of Sarrin on the Euphrates River. While few expect any sudden collapse, many analysts believe that, barring some error by its enemies that would win it a flood of new allies, IS may have already peaked in size and strength.

If hopes for a speedy resolution on the ground in Syria are dim, some see chinks of light on the diplomatic front, where the nuclear deal over Iran has focused minds on resolving other regional issues. When a large group of foreign ministers, including those of America and Russia, meet in Qatar on August 3rd, ostensibly to reassure Gulf Arabs about the nuclear agreement, Syria is sure to be on the agenda.

No comments:

Post a Comment