The Guardian

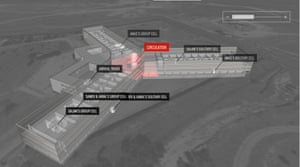

‘An architectural instrument of torture’ … a ‘satellite’ image of Saydnaya prison, based on an Amnesty reconstruction. Photograph: DigitalGlobe - Copyright 2016

Link

Samer al-Ahmed remembers the size of the small hatch near the bottom of his cell door because he was regularly forced to squeeze his head through it. The prison guards would then straighten it out, so his throat was pressed against the edge of the hatch, and jump on his head with all their weight, until blood started flowing across the floor.

It is one of the many methods of torture used in Saydnaya military prison, Syria’s most notorious jail, a hidden complex now brought to life in a harrowing interactive digital model as part of Amnesty International’s work to raise awareness of the darkest untold stories of President Assad’s brutal regime.

A black spot on the human rights map, the high-security prison has been off limits to journalists and monitoring groups in recent years. It stands 25km north of Damascus, near the ancient Saydnaya monastery where Christians and Muslims have prayed together for centuries. A mute concrete trefoil is discernible from Google Earth, standing in the centre of a 100-hectare desert compound. Nothing has been known about what goes on inside until now.

To coincide with the launch of a damning new report, which estimates that 17,723 people have died in custody in Syria since the crisis began in March 2011, Amnesty has collaborated with the Forensic Architecture agency at Goldsmiths, University of London, to reconstruct the site.

“As we pieced together the model, we realised the building isn’t only a space where incarceration, surveillance and torture take place,” says Eyal Weizman, director of Forensic Architecture, “but that the building is, itself, an architectural instrument of torture.”

Weizman’s provocative work – tagged “the architecture of public truth” – has tackled everything from the spatial strategies of the Israeli Defence Force in Palestine to mapping drone strikes in Afghanistan and the topography of genocide in the Guatemalan jungle. His team is practically unique in the field of “architectural forensics”, using the designer’s spatial toolkit to build damning bodies of evidence used in both UN investigations and trials in the international criminal court.

For Amnesty, the team began an intensive process of interviewing former detainees of Saydnaya prison who escaped across the border to Turkey, to build up a detailed picture of the facility.

“Architecture is a conduit to memory,” says Weizman, describing how an Arabic-speaking architect built a digital model on screen as detainees described specific memories and events. “As they experienced the virtual environment of their cells at eye level, the witnesses had some flashes of recollection of events otherwise obscured by violence and trauma.”

Inmates were constantly blindfolded or forced to kneel and cover their eyes when guards entered their cells, so sound became the key sense by which they navigated and measured their environment – and therefore one of the chief tools with which the Forensic team could reconstruct the prison layout. Using a technique of “echo profiling”, sound artist Lawrence Abu Hamdan was able to determine the size of cells, stairwells and corridors by playing different reverberations and asking witnesses to match them with sounds they remembered hearing in the prison.

“Like a form of sonar, the sounds of the beatings illuminated the spaces around them,” says Abu Hamdan. “The prison is really an echo chamber: one person being tortured is like everyone being tortured, because the sound circulates throughout the space, through air vents and water pipes. You cannot escape it.”

“Ear-witness” testimonies have become a crucial form of evidence, he says, citing the recent examples of the shootings of Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown, as well as the Oscar Pistorius case, where sound played a crucial role in unpicking what happened. “Unlike vision, sound leaks into other people’s spaces,” he adds. “People might not be facing an incident, but they can still have an acoustic experience of it.”

Deprived of their visual sense for months and years on end, the Saydnaya detainees developed an acute aural sensitivity, able to identify the different sounds of belts, electrical cables or broomsticks on flesh, and the difference between bodies being punched, kicked or beaten against the wall.

“You try to build an image based on the sounds you hear,” says Salam Othman, a former Saydnaya detainee, in a video interview. “You know the person by the sound of his footsteps. You can tell the food times by the sound of the bowl. If you hear screaming, you know newcomers have arrived. When there is no screaming, we know they are accustomed to Saydnaya.” During punishments, inmates were forbidden from making a sound. Any squealing only prolonged the torture.

Another detainee recounts details of the “welcome party” – the terrifying initiation ceremony that awaited new arrivals, fresh off one of the “meat fridge” trucks used to transport prisoners, clueless to their whereabouts until the doors clanged open. Beatings with metal bars and cables were followed by so-called “security checks”, during which women in particular were subjected to rape and sexual assault by male guards. “As we waited for our turn, we heard the sounds of beating, of people falling out of the truck, we heard people scream,” says Jamal Abdou. “Everyone was screaming – the guards and the prisoners.”

Abdou and Ahmed spent the first five months of their incarceration underground in a freezing-cold solitary confinement cell, a space just 2.35m by 1.65m, designed for one person but used to hold up to 15 people at a time, forced to take turns sitting down in the cramped room. They recall days at a time when the water was cut off, forcing them to drink from the toilet gutter, inducing hallucinations and waves of hysteria when the sound of water dripping through the pipes returned. “When I closed my eyes, I started seeing waterfalls,” says Ahmed.

The point of recreating this gruesome torture centre in such vivid detail, says Weizman, is twofold. It is not only a tool to induce further testimony, but serves as a powerful form of advocacy: “The aim is to get this place shut down and ensure that Assad is no part of any future peace deal.” Links on the Amnesty site direct readers to send a message to “tell Russia and the US to use their global influence to ensure that independent monitors are allowed in to investigate conditions in Syria’s torture prisons”.

“For years Russia has used its UN security council veto to shield its ally, the Syrian government,” says Amnesty’s Philip Luther, “and to prevent individual perpetrators within the government and military from facing justice for war crimes and crimes against humanity at the international criminal court. This shameful betrayal of humanity in the face of mass suffering must stop now.”

For Diab Serriya, who was imprisoned in Saydnaya from 2006 to 2011, the reconstruction serves as a lasting reminder.

“I lost five years of my life there, I nearly died there,” he says. “I just want it to remain so that other generations will see this horrible place, where we were tortured. The world should know it’s the worst place on earth.”

No comments:

Post a Comment