By David Hearst

Link

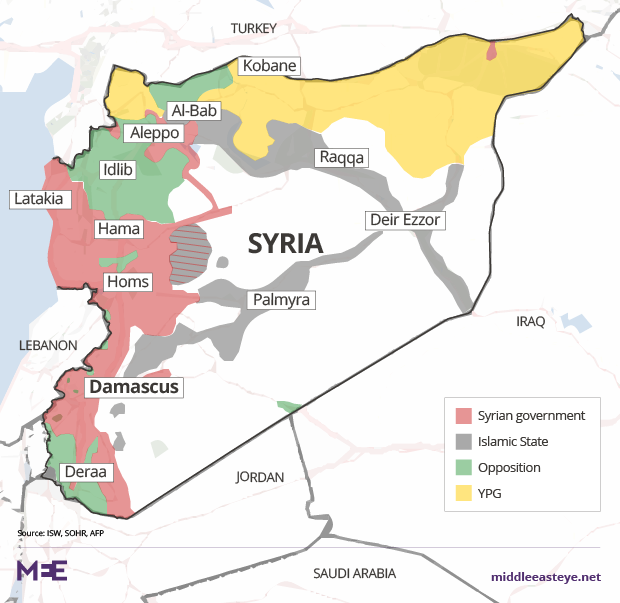

The big losers from the Turkey-Russian entente are Iran and the Kurdish YPG - with Saudi Arabia now left watching from the sidelines

Not so long ago, the question on many people’s minds was whom the US would choose as partners in the liberation of the northern Syrian town of al-Bab from the clutches of Islamic State fighters - the Kurds or the Turks.

That question has since been answered on at least two occasions. Turkish ground forces are getting air cover from the Russians as well as their own air force, and there is little either the US or their former allies in Kurdish YPG can do about it.

This was the way Sputnik, which took over from RIA Novosti as the official voice of Russia, and which at one point was banned in Turkey, reported the first three Russian air strikes around al-Bab:

“Euphrates Shield, a Turkish operation to defend its border from terrorists, received a notable boost from Moscow. Turkish military officials announced that Russian fighter jets eliminated 12 Daesh militants in air strikes… The US has been coy in supporting Turkey as Washington has backed the Kurdish YPG, a group that has long sought to create their own nation, independent of Ankara.”

Sputnik omitted to mention that Moscow supported the Syrian Kurds in that ambition, allowing them to open their first international office in Moscow. All that, of course, is now water under the bridge.

No longer interested

Welcome to the new world order - at least as far as Syria is concerned. The fall of Aleppo marked a form of regime change among those states who have pulled the strings of the political and military Syrian opposition. Exit the US and Saudi Arabia and enter Turkey.

When Syrian opposition leaders pulled out of the last set of peace talks in Geneva, there were calls from Riyadh instructing them on when to leave the hotel

Not so long ago, the Saudis choreographed the smallest moves of Syrian opposition. When Syrian opposition leaders pulled out of the last set of peace talks in Geneva, there were calls from Riyadh instructing them on when to leave the hotel.

In December, King Salman addressed his newly appointed Shura Council, the non-elected parliament, in what could be considered a state of the kingdom speech. This was a few days before Aleppo fell. Salman made not one reference to Syria in the section of his speech devoted to foreign affairs and only one scant sentence in a passage devoted to humanitarian work praising the Saudi campaign for the relief of Syrian refugees.

The omission was deliberate. The message Salman was sending Syrian rebels he had once funded and armed was simple: we are no longer interested. This clearly had implications for Turkey as well.

Wooing Turkey

Turkey’s disenchantment with Obama’s outgoing administration had been building steadily and reached a peak after the failed coup last year. For years, they asked for a no-fly zone in Syria and did not get it. For years, they asked for weapons that would allow the Free Syria Army to change the course of the war. Obama vetoed those, too.

Conspiracy theory or not, the majority of the government in Turkey believe that Washington either had a hand in the coup attempt in July or foreknowledge of it. Relations with Europe are just as icy, after the EU’s failure to deliver a visa waiver deal for Turkish citizens. This was one of several reasons which forced Ahmed Davutoglu to resign as prime minister.

Much of this is manna from heaven for the man who has become Erdogan’s closest foreign ally, Vladimir Putin. The Turkish file has become very important to Moscow, too important to be derailed even by the murder of a Russian ambassador. Turkey is the second largest army in NATO, the military alliance whose eastward expansion has sapped so much of Russia’s geopolitical strength. The possibility - still faint - that Erdogan can walk away from NATO would be a major achievement for Putin.

Putin has got what he wanted from his intervention in Syria. He has his base; the Syrian state has been saved, and the rebels have been so weakened, they are ready - or so the Russians calculate - to accept a deal on a transitional government which would keep Assad in place.

Risk of blowback

Russia is not interested in annihilating the Syrian rebels in Idlib, or in turning the vast majority of the Sunni Muslim population against them. The deployment of 400 Chechen military police - who are Sunni Muslims - in Aleppo was another product of the Turko-Russian pact, which was done at Turkey’s request.

The last thing Putin wants to do is to repeat the mistake George W Bush made in Iraq or indeed the Soviets in Afghanistan in which both invading forces won the war, but lost the peace

If Donald Trump feels he has a problem with his Muslims which form less than 1 percent of the population in America, Muslim minorities - mainly Tatars, Bashkirs and Chechens - form up to 14 percent of the population of the Russian Federation. There are a million Muslims in Moscow alone, which held one of the largest Eid celebrations anywhere in the world. The risk of blowback from Syria on the streets of Moscow is real, with or without video threats of sleeper cells in the Russian capital from the Islamic State (IS) group.

Russia’s interest lies in closing down the Syrian conflict sooner rather than later. The last thing Putin wants to do is to repeat the mistake George W Bush made in Iraq or indeed the Soviets in Afghanistan in which both invading forces won the war, but lost the peace.

Here Russian and Iranian interests diverge. Russia has never had a problem with Israeli air strikes on Hezbollah’s supply lines in southern Syria. Unlike Russia, Iran’s motives in Syria are ideological.

Iran is the brains behind Assad's plan to redraw the ethnic map of central Syria. They want to evacuate all Sunnis from their areas between Damascus and the Lebanese border. Iran has brought 300 Shia families from Iraq to repopulate the Damascus suburb of Darayya, which surrendered as an opposition stronghold in August. They have also shipped in Shia families to protect the Zainab shrine. Iran’s planning is strategic, long term and deeply sectarian.

Iran pushed for an all-out offensive on Idlib after the fall of Aleppo, arguing, so far unsuccessfully, that the rebels should be given no respite.

Winners, losers and a retreat

This, then, is the state of play in Syria that greets Trump on 20 January. Without him having to make a single policy decision, it is tailor-made for a new US rapprochement with both Putin and Erdogan - and all with Israel’s blessing.

The losers of Turko- Russian pact blessed by Trump will be Iranian-backed militias and the YPG. There have been tensions between Iran and the Iraqi Kurds, although with a group closer to Barzani's KDP, an Iranian Kurdish armed opposition group called the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (PDKI). They accused Iran of a bombing in Koy Sanjaq, a town east of Erbil, the capital of the Iraqi Kurdistan, which killed five of its fighters and a Iraqi policeman.

Last year saw the first lethal clashes for many years between PDKI fighters and the Iranian Revolutionary Guards in northwestern Iran. For now, the US-backed Syrian Kurdish forces of the SDF are still on the march to Raqqa.

READ: More columns by David Hearst

The de facto pact between Russia and Turkey to carve zones of influence out of Syria would have King Salman’s blessing. The Saudis were so terrified of the Russian intervention, the nuclear agreement with Iran and the Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Act (JASTA) in Congress, that they would do anything to keep in step with the new US administration. Their foreign policy is built first and foremost on fear. This was why they silenced their best journalist Jamal Khashoggi from even tweeting on the subject.

It is not, however, the end of the story. Neither Iran, nor Assad - both of whom want to press home their advantage against the rebels - will be so easily deterred, as the latest ceasefire violations around Damascus show. Having invested so much in their foreign intervention, Iran will not want to let Turkey stabilise and strengthen the Syrian Free Army under one unified command, as it now threatens to do.

Nor will the Syrian rebel factions be so easy to turn on or off. I do not share Moscow’s confidence that they will sit down with Assad in one room, let alone agree to him staying on. All we have witnessed is just another chapter in the long march of America's retreat from the Middle East.

- David Hearst is editor-in-chief of Middle East Eye. He was chief foreign leader writer of The Guardian, former Associate Foreign Editor, European Editor, Moscow Bureau Chief, European Correspondent and Ireland Correspondent. He joined The Guardian from The Scotsman, where he was education correspondent.

No comments:

Post a Comment