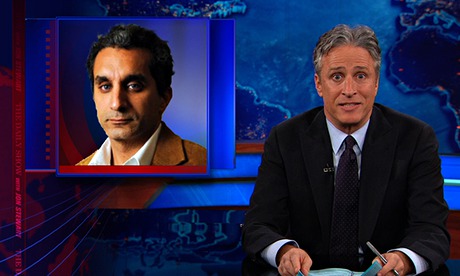

Jon Stewart presenting a Daily Show item about his friend and Egyptian opposite number Bassem Youssef

Three years after the pro-democracy protests began in Tahrir Square, freedom of speech faces a new challenge, says TV satirist whose show was blocked

"Early in November, millions of Egyptians switched on their televisions to watch the latest episode from the Middle East's most successful political comedian. But 10pm passed and Bassem Youssef did not appear. Instead, a newsreader read a statement from the channel's board:Youssef's show had been withdrawn.

It was a telling moment for free speech in Egypt, in the wake of the ousting of former president Mohamed Morsi. Youssef, a former heart surgeon, had become a poster boy for post-revolutionary Egypt in the months that followed the 2011 uprising. He was the most popular of the many Egyptians who took advantage of the freer political landscape to broadcast thoughts and jokes from their bedrooms to the internet. Youssef's satirical takes on politics first earned him millions of hits on YouTube, then the epithet of "Egypt's Jon Stewart", after the American satirist – before finally he got his own slick TV show, the first of its kind to feature a live audience in Egypt.

So when his own paymasters pulled Youssef's latest episode – the second of a new series that had lightly criticised many Egyptians' unthinking nationalism – many saw it as a sign of how the space for public discourse created by the revolution was vanishing fast under the de facto leadership of General Abdel Fatah al-Sisi.

According to Youssef himself, the show's cancellation was not a direct order by the army-backed government that was installed after Morsi's overthrow last July, but the product of an environment in which dissent is strongly discouraged. "You can always implement some sort of a mood, without actually giving direct orders," Youssef said in an interview with the Observer. "It is about creating a certain atmosphere that would make this acceptable or doable, and I think it reflects badly on everybody. Even if the people in authority do not do it, it reflects badly on the freedom of speech in Egypt."

In the months since Morsi's removal, the government and most of its media outlets have developed a narrative in which an authoritarian secular state is portrayed as the only buffer against political Islamists like Morsi. In this with-us-or-against-us atmosphere, people like Youssef, who question both options, are ostracised – or even smeared as terrorists. Earlier this month, up to 35 activists who dared to encourage people to vote against Egypt's new constitution were arrested, their actions portrayed as treasonous. Last week, two leading liberal academics – Emad Shahin and Amr Hamzawy – were placed under investigation after criticising first Morsi's regime and then the abuses of the Sisi era. On Friday, the hysteria reached farcical proportions when prosecutors reportedly began investigations into Pepsi because of an advert in which, officials claimed, the soft drinks company was inciting protest.

For Youssef, the irony is that this censorship exceeds the attacks on free speech under Morsi – attacks that were part of the reason millions called for the former president's downfall on 30 June last year. Youssef himself had been summoned by Morsi's prosecutors in April after some particularly provocative mockery. But his show was only pulled after Morsi fell.

"If we come up to 30 June saying that we want democracy, that we want to get rid of religious fascism, and then you see that this happens," Youssef said, "it really doesn't send a good message to the world."

The hypocrisy was crystallised by Youssef's television station, CBC, which had backed him wholeheartedly when he took on Morsi's government but abandoned him when he showed even a remote interest in taking on Sisi's. "There was an unlimited support from the channel before 30 June," said Youssef, who is in talks with a different station about taking his show elsewhere, but won't say which. "They were behind me every step of the way."

But after just one episode of Youssef's first post-Morsi series, CBC pulled the plug. "They said I was speaking about things I should not be speaking about ... insulting national symbols. But, you know, Morsi was the president: he was a national symbol."

Youssef puts the public abandonment of liberal principles down to the relief that many felt after the removal of Morsi, whose ideology threatened the identity and lifestyles of secular Egyptians. "It's like: thank God we got rid of the Muslim Brotherhood, we're not a jihadist Islamist republic – and we would do whatever it takes [to keep the Brotherhood from power], even if that means sacrificing a few liberties," he said. Like many of Morsi's critics, he is a devout Muslim – but rejects religious rule.

"People say that if it's going to be that bad, I would prefer it to be with this [non-Islamist] regime. Even if you compare the two extremes, a military dictatorship and an Islamic dictatorship – and I am not saying that we are in a military dictatorship right now – people are not threatened for having the same style of life. Whereas under the Islamist dictatorship, everything is questioned."

The mindset he describes is one he has not always entirely avoided himself. These days Youssef is one of Egypt's few public figures to voice concerns about the polarised nature of Egyptian society. But in the frenzied days following Morsi's overthrow, he was accused of contributing to the polarisation after claiming, in a tweet that he later deleted, that Morsi supporters had got themselves killed by police for publicity. A day later, he wrote a column defending – ironically – the closure of Morsi-friendly TV stations. It was another week before he took a more nuanced stance, encouraging liberals not to replicate the undemocratic tendencies of the Muslim Brotherhood.

Eight months on, Youssef maintains that his two positions were consistent. "There was no contradiction between the two articles," he said, sitting in his office, decorated with pictures of his friend and mentor, Stewart, in a restored cinema in Cairo.

"The first article basically said that if 30 June had not happened, the Muslim Brotherhood would have taken us, and they would not have shed a single tear. There were already warrants: they were going to close our channels, it was either us or them. Then I spoke to 'us', the quote-unquote 'victorious us', and I said: you know what, why don't we show grace? We already won, please do not repeat the same mistakes that were the reason that we took against the Brotherhood. It was not a contradiction. If we go back, I would still choose what happened on 30 June."

But evidence from his latest series suggests Youssef is unhappy with what has gone on since. "I don't support the hypocrisy, deification, pharaohisation, and the repetition of the mistakes of the past 30 or even 60 years," he says during its most controversial sequence, in a veiled reference to the dictatorships of Hosni Mubarak, Anwar Sadat and Gamal Abdel Nasser, a strongman era to which some seek a return. "What we fear is that fascism in the name of religion will be replaced by fascism in the name of patriotism and national security."

Many were outraged, and there were even protests outside his studio. But for a few revolutionaries, Youssef did not go far enough. Under Morsi, he took on the man. But Youssef would not pick on Sisi personally, just the mentality of his supporters.

Youssef thinks he struck exactly the right balance. "For those people who said I didn't go far enough, obviously it was far enough for my programme to be stopped," he smiled. "And for the other people who said I went too far, well, compared to what I did under Morsi, it was not even close."

In Youssef's ideal world, people would just view him as a commentator – much as Jon Stewart is viewed in America – rather than as a politician in his own right. "I'm just a watcher," he sighs. "I'm just a spectator. I'm not into this game. I'm not a political player."

But in a polarised Egypt, three years and a day after protests began in 2011, it may not be Youssef's choice.

No comments:

Post a Comment