'Hosni Mubarak thought he could ignore popular protest. He was wrong. Mohamed Morsi, the Muslim Brotherhood president, made the same mistake.' Illustration: Simon Pemberton

The old regime has morphed into a new form under Sisi, yet our young activists know the rot that lies at its heart

After the presidential elections there's a subdued air about Cairo. Flag-sellers wave their leftovers at passing traffic: half-price flags, but nobody stops. In the Tahrir wilderness, unrecognisable now from the swirling, buzzing, gallant place it was three years ago, a man stands alone at the edge of the central island. He is old and silent, and he carries a banner with a picture of the new president and the legend: "Congratulations Egypt!"

A camera stands on a tripod with nothing much to film. A knot of people is gathered nearby. They are in a kind of rugby scrum, and it's impossible to make out what they're doing. Cars honk impatiently and refuse to give way to one other. Two elderly men yell angrily from the window of a car with posters of the president-elect, Abd el-Fatah al-Sisi, plastered all over it. Sisi supporters should be happy, yet they seem angry, their shouts scolding the passersby rather than inviting them to share the joy.

Like a sci-fi monster, the blocks of the old regime break and dissolve only to rise again in a new configuration. In the later Mubarak years, the president held the balance and the peace between his family and their capitalist cronies on the one side, and the military on the other. The security establishment served the president and his friends, with no love lost between them and the military. As the government abandoned its responsibilities in education, health and social services, the Muslim Brotherhood picked up the slack. It built up its own web of patronage, never challenging the government enough to scupper the deals over seats in parliament and opportunities to make money.

Now the building blocks are morphing into a new arrangement. The military have been voted into the presidential palace. They are trying to build bridges with the security establishment; they need them to quell dissent. They've made themselves the channel through which Gulf money will come into the country, and they'll use it to establish a network of business cronies. The Brotherhood is out in the cold, ousted last July and declared a terrorist organisation, but it would probably be allowed back in if it settled for its old, compromised opposition role.

And what of the biggest block of all, the people? Hosni Mubarak, in his later years, thought he could ignore popular protest. He was proved wrong. Mohamed Morsi, the Muslim Brotherhood president, made the same mistake – to his cost. Field Marshal Sisi courted the people, crooned to them. But the wafer-like thinness of this amour was exposed on the first day of presidential elections, on Monday, when the masses failed to show up. Television anchors and media celebrities became hysterical, berating, lambasting and insulting the Egyptian people for their "apathy".

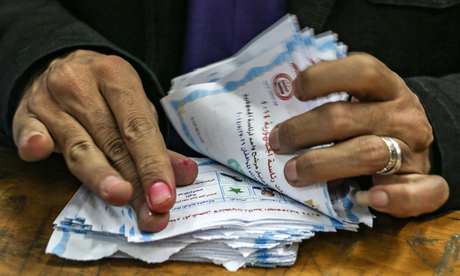

By day two – hastily declared a holiday – huge speakers mounted on patrolling vans alternated love songs to the military with rants at people to "leave their air conditioning" and come out and vote. Shopping malls closed early. The government swore it would fine non-voters half a month's minimum wage. Even so, they had to extend voting to a third day to get the numbers.

‘The government swore it would fine non-voters in the presidential election half a month’s minimum wage. Even so, they had to extend voting to a third day to get the numbers.' Photograph: Asmaa Abdelatif/Xinhua Press/Corbis

‘The government swore it would fine non-voters in the presidential election half a month’s minimum wage. Even so, they had to extend voting to a third day to get the numbers.' Photograph: Asmaa Abdelatif/Xinhua Press/Corbis

The regime would like to have danced us round in a full circle, picking up some revolutionary glitter along the way. But it hasn't. We are not on level ground. We are on a spiral. Everything that was, is more: brutality, injustice, poverty, anger; but also clarity, knowledge, understanding and, possibly, determination.

Are we in a worse place than we were before 25 January 2011? Our loss, the grief of which is immeasurable, is the thousands of people murdered and maimed, and the years tens of thousands have lost, and are still losing, in unjust imprisonment. Every tally has to start with these.

And it's hard to tell what comes next. Perhaps the president, chastened by the elections, is working out how he can balance the demands of the people with the interests of his backers. The people who descended on Tahrir on Thursday night were there to celebrate, but they could easily turn. The revolution has shown us the rot at the heart of the regime, it has brought discontent to the surface. It has expressed the urgency and intensity with which the young desire a different system, and it has shown that they have the ability and the energy and the inventiveness to create it. They just don't have the space to try, and they don't have the power to make that space.

The revolution proved that a framework enabling people to self-organise in small but coordinated communities will empower them and set free their creative energies. This is of interest not just to Egypt but to the young across the world. Yet the political system is built on the opposite idea – of people coalescing around leaders in hierarchies. The struggle is to invent a new system while the old one is attacking you, bad-mouthing you, murdering and imprisoning you.

Watching the young and listening to them during these last few days of untrammelled deceit, vulgarity, inefficiency and jingoism, I brimmed with admiration: friends jailed and murdered, dreams mutilated, exhausted beyond limit, they were still astute, clear-eyed and funny. They may have lost this round, but they're no losers.

No comments:

Post a Comment