The first the crew of the Antarctica knew of the disaster was a radio request to help a search and rescue operation. There were bodies in the water 200 miles off the coast of Malta. Two other ships – the Verdi and the Japan – were already at the scene, picking people out of the sea. The Antarctica was swiftly diverted and took command until the arrival of coastguard and naval ships.

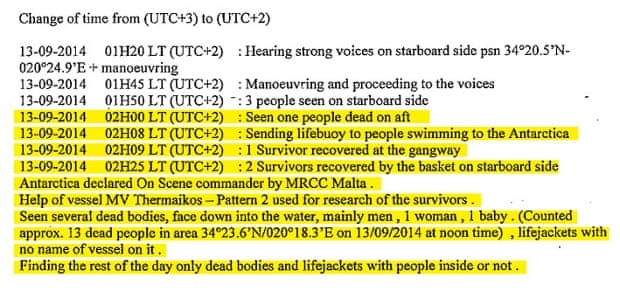

The timesheet of the rescue makes for chilling reading, a catastrophe recounted in staccato phrases.

The Verdi picks up four people in the water, the log recalls, but one of them is dead. An empty liferaft is spotted. And then a body in the water. A woman and two children are rescued by the Japan.

A few hours later, the crew of the Antarctica hear voices. Three people are retrieved. Over 24 hours, 11 people would be plucked alive out of the waves, a two-year-old girl among them, and taken to Malta, Crete and Italy.

One of the survivors was Hameed Barbakh. A resident of Khan Younis in southernGaza. He would later describe to the Guardian the tragedy that so nearly cost him his life. In perhaps the most egregious episode yet of a deadly year on the Mediterranean, a fishing boat packed with hundreds of migrants had been rammed by another smuggling vessel when those on board refused to get on a smaller boat. As hundreds drowned, Barbakh survived by clinging to a lifejacket he found near the wreck.

His story meshed with those of other groups of people from Gaza whose relatives were caught in the grim incident. Their stories illuminate two startling new details about the perilous Mediterranean odysseys which this year have claimed the lives of more migrants than ever before. The first is that as well as countless Syrians, Afghans and Africans trying to make the perilous journey, a surprising number of refugees are from Gaza. The second is that in order to escape, they must put their lives in the hands of a wealthy, influential and ruthless smuggling gang. Rarely has the expression “devil and the deep blue sea” seemed more appropriate.

Khan Younis, Gaza

A few weeks before the sinking, the main street of Abasan Jadeed, on the eastern edges of the southern Gaza town of Khan Younis, was on the frontline of the most recent war with Israel, scarred by shrapnel and bomb craters. These days, however, it is the locus of a different tragedy.

Three households within the space of a few hundred metres are coming to terms with a new type of grief every bit as shattering as the recent war. Seven members of three families are missing following the sinking.

And not just in Abasan Jadeed. Across Khan Younis and the neighbouring city of Rafah on Gaza’s southern border with Egypt, in Gaza City and elsewhere, desperate families are seeking news of the missing. Some put the number at more than 200, mostly young Gazans trying to flee a life that had become “unbearable”. Gaza has been crushed by three wars with Israel in the past six years, and decimated by seven years of economic blockade. Prospects for the 1.7 million people living on a strip of land less than one-third the size of New York City are vanishingly small. People want out.

On the second floor of an apartment block, Nawal Asfour is waiting for news of her son, Ahmad. It is the third time she has had to confront the fear that she might lose him.

The first, she explains, was when Ahmad, then a teenager, was critically injured by a missile in the last days of Israel’s war against Gaza in 2009.

Ahmad lost three fingers on one hand, a section of bone in his arm and his pancreas. She thought she had lost him again when he went to Israel for treatment, only to be arrested at the border and jailed for three years on suspicion of being a member of Islamic Jihad.

Nawal, who has cancer, is not convinced there will be a third reunion.

In some respects Ahmad personifies the story of Gaza: hopeless, angry, unable to recover; desperate to be anywhere but within its narrow confines.

“He was sick to death of how things were for him here,” says Nawal. “He never really recovered from his injuries. Someone said to him if he could get to Europe, he could get free treatment.”

So Ahmad, who had returned to Gaza from Israeli prison in 2012, crossed the Rafah border into Egypt with three members of his family who had been injured during the most recent war with Israel, taking advantage of Egypt’s agreement to allow medical evacuation. In Cairo he called to tell his family he needed money to pay for hospital treatment. Only later did they realise he needed the $2,000 (£1,200) to pay an infamous broker based in Alexandria, a man nicknamed Abu Hamada who is well known for getting people from Gaza through Egypt and the Nile Delta town of Damietta, and onwards to Italy.

And it is not only the Asfours who are looking for missing family members. Across Gaza last week families were looking for relatives, most of whom had been smuggled through tunnels into Egypt. If, for a brief period, Gaza’s secretive illegal railroad to Europe had been spoken of as a source of hope, now it inspires only fury and bitterness.

The families of the missing are angry at the people smugglers, and angry at Hamas and the Palestinian Authority. Their ire is directed too at a Europe they say has done too little to help them find their relatives.

“I was worried about Ahmad because he has no pancreas but they said they would keep an eye on him,” said his father, Samir. “Then four days later my son who lives in Germany got a phone call from Ahmad, who said he was on the ship and a day from landing in Italy. That was the last we heard from him.”

The tunnels

On the road to Rafah, at Gaza’s southernmost end, sits an unfinished mansion, empty and incongruous amid the general dereliction. It stands as a testament to the boom years of Gaza’s smuggling business with Egypt, when a canny tunnel operator could get rich transporting anything from cars to cattle and household goods.

It is a trade that relied on Egypt at least turning a blind eye, not least during the brief rule of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi. Those were the “good days”, remembered fondly in Gaza, when its economy boomed briefly. But following Morsi’s removal in a military-led coup in July 2013, Egypt clamped down on the flow of goods through Gaza’s tunnels.

And so the tunnel operators turned to a different, but equally lucrative, business – moving people out of Gaza rather than smuggling goods in.

The tunnel entrances are on the outskirts of town, running under the sandy hinterland next to the border: steep narrow shafts shored with concrete or timber connecting to claustrophobic passages that lead to Egypt. Although it was known that people could move through the tunnels, the scale of the exodus remained unclear, until now.

Off a sandy lane in Rafah lives Abu Fadi, a tunnel operator who sent two of his sons to Sweden before the latest 50-day war . He says he is not in the people smuggling game, but knows those who are; many are under house arrest, punished by Hamas for their part in a business that has shown Gaza in a poor light.

“The people who own the tunnels fake the stamps,” Abu Fadi explains. He says this costs about $100, while passage through the tunnels costs another $400-$600. He adds that despite the fact tunnels are under Hamas’s control, it was easy to sneak people through; indeed, the latest conflict with Israel made it easier still as Hamas was distracted.

Hameed Barbakh also knew of Gaza’s smuggling tunnels before he decided to escape. Speaking from Italy, he explained he had even worked in them until the business of moving goods into Gaza was thwarted by the new military regime in Cairo. Unable to earn enough money to rent somewhere so he could marry his fiancee of six years, he headed to Europe in search of a better life. Like Ahmad Asfour, the people-trafficking contact he sought out was Abu Hamada and his agents in Gaza. “My first contact was a man who works with Abu Hamada,” explained Barbakh. “That’s who arranged to take me through the smuggling tunnels out of Gaza.”

For many of the missing the journey to Egypt starts at dawn. In the early morning gloaming, they descend into the network of subterranean passages that span the few hundreds metres across the Gazan border, into Egypt.

Through the Sinai

For the migrants emerging from the tunnels, the contrast is stark: from one of the most overpopulated places on the planet to the barren expanse of Sinai.

The first stop in this arid place of poor farms and orchards clinging to the dry soil is Rafah, cut off by the border from its Palestinian counterpart.

According to those who have made the journey, the first destination is a safe house owned by friendly Egyptians. Then a driver, supplied by the smugglers, takes them to Arish, the regional capital, via back roads that avoid the military checkpoints blocking the roads of north Sinai. The fake immigration stamps in their passports will help if they are unlucky enough to hit a roadblock.

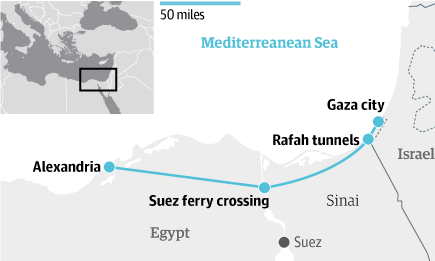

In Arish, there is a change of cars to vehicles that take them all the way to Alexandria. They cross the Suez canal by ferry with few questions asked and reach Alexandria, normally within 12 hours of leaving Gaza. Sometimes the journey is rapid. According to accounts given to the International Organisation forMigration (IOM), three of the survivors picked out of the sea by the Antarctica – Ibrahim Awadallah, 25, Mohammad Awadallah, 23, and Maamon Dogmoush, 27 – emerged from the tunnels on Friday 12 September and were in Alexandria within a day of leaving Gaza, and at sea within another.

Alexandria

There are good reasons why Alexandria has become a hub for those wanting to flee Gaza and Syria, and for other migrants trying to reach Europe, Egyptians and Africans among them. Its sprawling, ugly suburbs of crumbling high rises – like Miami and Palm Beach – are full of anonymous apartments in even more anonymous blocks, where landlords don’t ask questions for the right money, and where it is easy to hide those wishing to make the perilous journey to Italy. Equally important is its location. To its east and west are empty expanses of shoreline where small boats can come in close to shore and ferry those waiting to larger boats outside the coastal waters.

Hameed Barbakh takes up his story. “I was told when I reached Alexandria there was a place where I should go and wait to meet Abu Hamada’s people. After 10 minutes a man came and took me to an apartment with four others from Gaza. We waited for four days.”

In other apartments, unknown to Barbakh, were hundreds of others waiting to make the same journey arranged by Abu Hamada. Among them were Tariq and Osama, two fathers from Syrian refugee families who had escaped to Egypt. Arrested on a beach near Damietta on 6 September, they would be in prison when the migrant fishing vessel was rammed and sunk.

Like the Palestinians from Gaza, the smuggling network they had been put in touch with was the one run by Abu Hamada, reputedly a Palestinian-Syrian, who lived in Yarmouk refugee camp in Damascus before the Syrian war who has become rich as a broker in the people smuggling business.

“They say he was just a normal guy in Syria,” Osama said after his release from detention, “but here he’s become very rich.” And not only rich, but a man reputedly with powerful connections in the police and security services.

Osama fills in more details – the numbers and names of the smuggling network supplied to the Guardian in Gaza: “Abu Ahmad”, also known as “Ibrahim”, another member of Abu Hamada’s close network; “Nizar al-Baba”, a Syrian, and an Egyptian known as “Ahmed”.

Beyond this group of wealthy brokers, there are more shadowy figures: boat operators and smugglers who make the Mediterranean crossing, in this case a ruthless figure known as “the Doctor”.

For Tariq and Osama – the latter of whom had sold his wife’s jewellery to make the trip – the wait for their ship was a long one. After five days in a suburb of Alexandria they were ferried with dozens of others in five curtained coaches to near Marsa Matrouh with masked smugglers in cars accompanying the coaches.

That day the smugglers said the weather was too bad, so they returned to Alexandria, to another block of flats, a routine that would be repeated for days.

“They fill five buses,” said Osama,” but only one or two reach the beach. It’s very well known that two buses get to reach the sea, and two end up with the police. So we knew there was a possibility we’d end up with the police.”

Damietta

On 6 September in the separate apartments where they were being kept across Alexandria, Ahmad Asfour, Hameed Barbakh and Osama and Tariq received the same message. Once again, Abu Hamada’s men informed them, they would be getting on coaches and trying for the beach. Hameed got on his bus at 2pm. Ahmad boarded at roughly the same time, calling to tell his family he would be sailing for Italy that night.

Osama and Tariq were also picked up later that afternoon. But this time the convoy of coaches headed in a different direction, east towards Damietta.

Osama and Tariq’s bus stopped first at a garage in Abis, south of central Alexandria, where they changed coach. During the trip, they recall, an argument ensued between two smugglers on the convoy about money and shots were exchanged before the argument was settled.

At about 9pm – a timing that meshes with Hameed Barbakh’s account of his journey – they arrived at a roadside cafe near Baltim, close to Damietta.

Milling outside the cafe, the migrants were by turns cautious and excited. For some, this was their first time at sea. For others, it was the 10th or 12th attempt, and they knew the risks of what was to follow.

The smugglers did little to calm their nerves, shuffling people between buses according to how much they had paid in additional bribes. Those who paid extra got to sit at the front, allowing them first access to the beach. Those who had not, sat at the back, raising the likelihood that they would be arrested while waiting their turn on the shore. Two or three coaches left almost immediately, but Osama and Tariq had to wait until about 11pm, when they were driven closer to a beach.

Disembarking beside some disused buildings, the Syrians strapped on their lifejackets and carried their smallest children on their shoulders. To get to the beach, they were hustled through a small gap in a fence that lined the sand. Struggling with their luggage, they could see dozens of migrants streaming ahead of them to the shoreline. People were wading towards two small boats bobbing in the waves several metres from the shore. There, they were close enough to see people in the water, wading up to their shoulders, to reach two boats. Among them, they say, were many Palestinians.

But Osama and Tariq did not make it to the water. Instead they were arrested waiting for their turn to reach the boat. The two men suspect the police and Abu Hamada were in cahoots. Others familiar with the people-trafficking business agree. “On the first day when we reached the police station,” says Osama, “the police asked: ‘Who are the smugglers?’ I told him Ibrahim, Abu Ahmed [from Abu Hamada’s network] and I looked at the report that they were writing, and they wrote a made-up name: Faras el-Syrian. Maybe the police told them that I told their names, but Ibrahim and Nizar called me on Viber and said they knew that I had said their names, and that if I repeated it again, they’d send people to kill me, my wife and my children. They said: ‘We can reach you wherever you are.’ They are the worst kind of humans. They don’t value anything apart from money. They don’t care about women, children – they just want money. Lives aren’t important. They considered us dollars.”

At sea

Unlike Tariq and Osama, Hameed Barbakh made it to the boats. He recognised others from Gaza, including many families. “Over the next four days we were transferred to four different boats. The last was the largest. It was between 16 and 20 metres long. We brought our own lifejackets. There were people from Gaza and from Yarmouk in Syria. I can’t say how many, perhaps 500. By accident I met a friend I didn’t know was travelling.”

On the fourth day, he says, a smaller boat drew up alongside the ship. “There were members of the smuggling gang on the ship with walkie-talkies. They said we had to get into the smaller boat because the big one risked being confiscated in Italian waters if it was caught. But the captain said we would not all get into it and it would sink. So we refused.”

“The smugglers argued with the captain,” Hameed added. “They threatened to kill his family. But he was a good man and kept going. Then after a while our boat was rammed by a larger boat that was trying to stop us.”

According to accounts from other survivors compiled by the IOM, it is believed more than 300 people who were below decks when the ramming occurred drowned in minutes. Many others were lost in the following hours.

In his police statement, given at the Safi detention camp in Malta, Maamon Dogmoush told a similar story. “A fishing boat approached and told us to stop. They also threw a metal object at our captain and this same boat then came close to the side of our vessel and hit our boat. As a result, our vessel capsized and this fishing vessel kept on circling us and laughing.

“I think this boat was from Egypt. [It] was blue and had a number, 109. There were 10 people on this vessel and from their accent we could tell they were Egyptians from Damietta. This was confirmed by our captain who, before he died, told us these people were from that town because of their accent. Within a few seconds, our vessel sunk and the other fishing vessel left.”

“I found a lifejacket in the sea,” recalls Hameed. “Then I started swimming. I was in the water for two days before a ship spotted me and called the Italian navy. When they found me I was exhausted and vomiting blood.”

According to the families in Gaza, Abu Hamada and his associates first attempted to deny that those travelling with his network had been involved in the tragedy. Later, they say, he admitted some of his “clients” were killed.

When the Guardian called Abu Hamada in Alexandria he hung up, but his associate Nizar al-Baba agreed to take a call. He says only 30 clients were on the boat and that he and his team could not be held responsible for what happened.

“The boat that sank collected lots of different people [from different boats]. We are only responsible for the small boats [that took people] from the shore. We are not responsible for what happened at sea. You know there’s piracy that goes on at sea.” He claims too that – until now – his business has been “safe”.

“This is the first big accident that happened to people who left through Egypt. Previously the coastguards might have fired on a small boat of 10 or 15 people, or one or two people might have drowned, but a big one like this never happened to an Egyptian boat before,” he added. “I do feel sorry for the people who died and want to know what exactly happened to them … I have received threats from Syrian families who consider me responsible for the death of their loved ones, which is not true. They say that the blood of the dead people is on my neck.”

Additional reporting by Hazem Balousha in Gaza and Manu Abdo in Egypt

No comments:

Post a Comment