Bashar Assad is weaker than ever; but peace is not nigh

The Economist

IT IS hard to find a sitting ruler with more blood on his hands than Syria’s Bashar Assad. The war, sparked largely by his heavy-handed response to protests in 2011, has killed over 200,000 people and displaced half the population of 24m. In the 15 months to March this year, 3,124 civilians were killed by the regime’s bombs in Aleppo alone, according to an independent report this week. But now there are signs that his regime may be faltering.

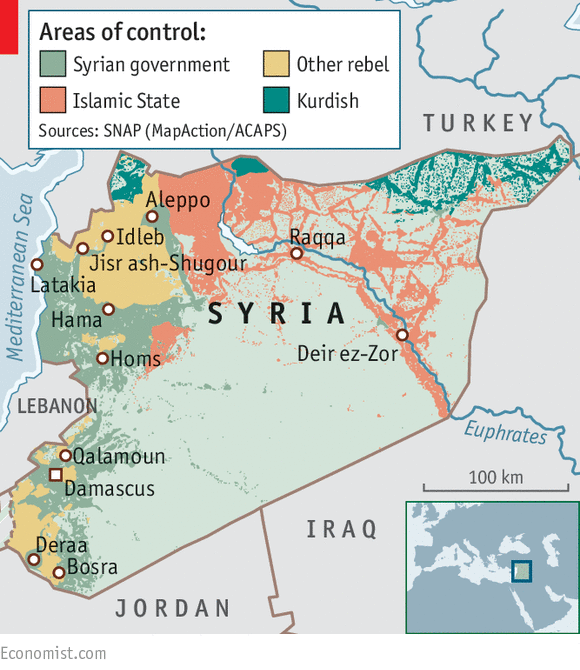

A year-long equilibrium in which the regime and its backers (Iran, its Lebanese client, Hizbullah, and Russia) had the upper hand has come to an end. Last month Mr Assad lost Idleb and Jisr al-Shughour, two key towns in the north-west, to rebel fighters. On May 4th a suicide-bomber made it into central Damascus, the heavily guarded capital. Latakia, the port city close to the Assads’ ancestral home, is now within the range of rebel mortars.

The regime is short of men, despite its use of foreign militias. Hizbullah and Iranian forces have withdrawn from some areas in the south of the country to protect Damascus and the border with Lebanon where Jabhat al-Nusra, a rebel group affiliated to al-Qaeda, launched an offensive on May 4th. Syrian soldiers grumble about being used as cannon fodder. A recent fight between two security chiefs, the subsequent mysterious demise of one of them, and rumours that a third is ill, all hint at disagreements in the ruling cabal.

At the same time the rebels, most of whom are Islamists, have become more organised both on and off the battlefield. Several groups, including Jabhat al-Nusra, banded together as Jaish al-Fatah (Army of Conquest) to take—and try to administer rather than run into ruin—Idleb. Deraa, the southern city where Syria’s uprising first began, is now within their sights. Aleppo, the recent target of a big regime offensive, now looks more likely to fall under full rebel control than into the regime’s grip.

The rebels are getting more of a helping hand. Their foreign backers, whose fractious relations have long hampered the effectiveness of their support, now appear to be better co-ordinated. Saudi Arabia, more assertive under King Salman, has reached out to Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Turkey’s president; co-operation with Qatar has also improved. “The takeover of Idleb was a sign of these changing dynamics,” says Lina Khatib, the head of the Carnegie Middle East Centre, a think-tank in Beirut.

Is this likely to translate into an end to Syria’s misery? Alas not. Militarily, it is still the case that neither side can prevail. The regime can survive by further confining its area of control to the western area of the country, where its grip is firmest.

A political solution looks just as improbable. On May 4th Steffan de Mistura, the UN’s envoy to Syria, embarked on fresh talks in Geneva with parties including, for the first time, Iran. That is a step forward; but in a backward one, the parties will not meet face-to-face as they did in two previous sets of talks. Western diplomats say the aim is to take stock rather than to broker peace. “I don’t see any signs of a breakthrough,” says Robert Ford, who was American ambassador to Syria when the uprising started in 2011.

Mr Assad is still unwilling to make concessions, and the rebel groups refuse to let him have any role in a transition. He still argues, with a degree of justification, that he is fighting savage terrorists; he has sent diplomats to Tehran and Moscow, and gone on a charm offensive with the press.

Despite seeing Mr Assad as something of a embarrassment, there are no signs that his backers want to be rid of him yet. In a speech on May 5th Hassan Nasrallah, Hizbullah’s leader, denied any intention to desert Mr Assad; and he has reportedly predicted the demise of Hizbullah itself if Mr Assad falls [One Can Only Hope!]. And should sanctions on Iran be lifted after an agreement on its nuclear weapons at the end of June, Mr Assad’s main ally may only become more expansive. For its part, Russia has little traction with the regime.

The biggest pressure on Mr Assad may come from the economic problems affecting him and his allies. The drop in the oil price has hurt Iran and Russia. Iran has yet to provide credit to Syria this year, including $1 billion that Syria’s central-bank governor says Iran promised. Damascus’s desperation for cash was clear in recent announcements that private companies can bid for state assets and that Syrians can renew their passports (for a fee) without clearance by the security agencies.

The danger of complete chaos rises with every day the war continues. “State institutions have been the victims of the war,” says a former Syrian official. The army, bureaucracy, hospitals and schools have given way to militias and civilians struggling to survive. If the regime suddenly unravels, there will not be much to hold the country together.

No comments:

Post a Comment