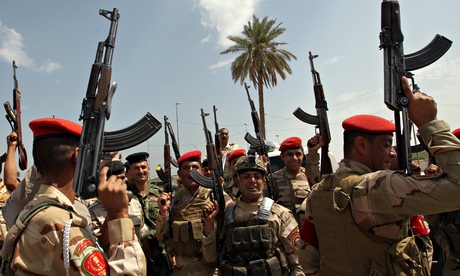

Iraqi army troops chant slogans against Isis as they recruit volunteers to join the fight against a major offensive by the jihadist group in northern Iraq. Photograph: Ali Al-Saadi/AFP/Getty Images

In December 2011 a band played quietly in the corner of a Baghdad military base as American soldiers lowered three flags and solemnly carried them away. Within minutes, the remaining US commanders had boarded a plane and left Iraq – with Washington vowing they would never return.

It wasn't quite a Saigon moment, but the scene did capture the essence of America's nine tumultuous years; great expectations, crushing lows, a pyrrhic victory. Then a low-key retreat.

Three and a half years later, it is as if the US military never left. Iraq has suddenly found itself in early 2006 again, in a week that has seen Sunni insurgents once more face off with Shia militias, a major city looted as an army stands by, and the two shrines whose destruction sparked the sectarian war again endangered. This, though, is a crisis like no other for Iraq, eclipsing even the blood-soaked and hopeless war years that pitched sects against each other and whittled out towns and cities. There is no occupying army to hold the country together this time. After the stunning capitulation at the hands of Sunni insurgents this week, there is barely a military left at all.

Late on Thursday, as Barack Obama spoke of sending US assets back to the country to save it from the abyss, Iraqi officials were almost begging to be rescued from gunmen sweeping the country almost unopposed and fast descending on Baghdad.

The group, known as the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Isis), has seized the second biggest city, Mosul, Saddam Hussein's former stronghold, Tikrit, and chased the Iraqi army out of the most bitterly contested city in the land, Kirkuk – allowing triumphant Kurdish forces to enter and seize control.

"They came to stay," said an Iraqi police captain in Kirkuk, reflecting the profound shift in the balance of power between Irbil, the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan, and Baghdad. "They are not going anywhere soon," he said.

Worse was to come on Thursday, when Samarra – home to the Imam al-Askareen shrines twice blown up by al-Qaida in 2006 – saw its military protectors capitulate. All it took was several phone calls from insurgents at a nearby checkpoint to spook troops in the town.

Within a day Shia militias from Baghdad were rushing to guard the shrines alongside the few soldiers who had stood their ground. The countryside nearby erupted in clashes between Isis operatives and Shia militias, who were at the vanguard of the civil war fighting.

"[Iraqi president Nouri al-] Maliki's tongue has turned white from fright," said one senior Iraqi official. "He is finished. He has nowhere left to turn."

Since Thursday at least three divisions of the Iraqi army – close to 50,000 men – and other smaller units scattered around the northern countryside have refused to fight, shedding their uniforms, selling their service weapons and buying dishdashas (robes) to blend in with civilians as they fled.

The extraordinary scenes have quickly revealed the fault lines running through post-US Iraq and the fragile ties that have bound together the ethnically diverse country since the fall of the Ottoman empire.

Iraq's military is majority Shia, while Mosul and Tikrit are predominantly Sunni. The two sides haven't often got on since 2006, despite periods of co-operation.

The sectarian enmity that festered during the war years has been reignited by the war in Syria, which pitches a Sunni majority against an Alawite minority with links to Shia Islam. Here and now grievances, amplified by historical unfinished business, are seriously testing the post-Ottoman borders.

Isis has made no bones about its intent to rewrite them. It already controls much of the border between Iraq and Syria and aims for the same control between Syria and Lebanon. And as great cities fell this week with little more than a gentle push, the jihadists seem on their way to their goal.

With his authority crippled and his army on the run, the president is the last person able to rally the country. After a finger-waving speech early in the week, in which he blamed conspiracies for Iraq's predicament, Maliki hasn't re-emerged.

Many say it is a problem of his own making. His leadership style has rarely been inclusive and is often polarising. A mandate he won in 2010 was unconvincing and his pledges to re-enfranchise Iraq's Sunni, who lost their power base when the US ousted Saddam Hussein, have never been honoured.

Maliki has spent the past six weeks trying to assemble a coalition that will gives him a third term as leader. This time round he has retreated to his sectarian base, leaving Sunnis to accuse him of using the army as a sectarian militia and co-opting the state at their expense.

Other figures, also active during the US occupation and the turbulent time since, have instead returned to the fray. First among them is the elusive Iranian general, Qassem Suleimani, whose elite Quds Force of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards had the Americans on the run from 2006, and have played a lead role in running Iraq and Syria ever since.

Suleimani arrived in Baghdad early on Friday. He spent the day in meetings with the leaders of his proxy militias, including Qais al-Khazali, from the much-feared Asaib Ahl al-Haq, Iraqi parliamentarians (Maliki wasn't on the list), and Sunni Sheikhs who control parts of Baghdad's outskirts.

His meetings suggest that he will play a lead role in organising the defence of the capital – a role that reaffirms his primacy in Iraq's strategic affairs.

"Isis are also strategically very capable," said the senior Iraqi official. "They are planning to enter Baghdad using the same routes that the Americans used when they entered [in 2003]. No one has faith anymore in the Iraqi military. Their work has been outsourced to Iran."

Obama, apparently also stirred into action by Iraq's existential crisis, signalled he is now willing to do what he had earlier vowed not to. His statement that there were "short term, immediate things that will need to be done militarily", was interpreted by Iraqi leaders as a new willingness to give them what they want – air strikes and drones.

"This group is a threat to US national security," added Obama.

The unlikely alliance of interests between Iran and the US in Iraq comes after a nine-year proxy war on Iraqi soil, which saw militias directed by Suleimani account for around one quarter of US battle casualties. As the US disengaged, Iran stepped in and, in the years since the US withdrawal, has acted as an overlord in neighbouring Iraq.

Iran has been determined to protect its arc of influence, from Tehran, through Baghdad, Damascus and southern Lebanon. The US, meanwhile, has tried to change the way it projects itself in the region, without letting its arch foe get the better of it, or its allies. "That's a battle it hasn't won," said a regional western ambassador. "Iran has been privately gloating, while America's friends have been publicly scathing."

Iraq, though, is a disaster that has rattled both foes. "Already the CIA have sent more than 150 men back here solely to look into Isis," the Iraqi official said. "What they give us, Iran finds out about soon enough."

Throughout the chaotic three years of the Arab spring, a potential redrawing of the regional map has always loomed large. The recent gains by Bashar al-Assad's army in Syria, supported fulsomely by Suleimani, who has spent much of the past two years in Damascus, had doused such fears. But Iraq has rapidly rekindled them.

"What is going to hold this country together?" one cabinet minister asked. "We cannot stand on our feet. We have to turn to the heavyweights. Iraq has not emerged from the fog at any point after Saddam."

The sheer scale of the Iraqi military's capitulation in the face of a well-armed and disciplined insurgent force has shocked American soldiers and officers who fought in Iraq. Many were involved in training and mentoring Iraqi counterparts and left the country thinking they had helped build a credible institution, perhaps the only one in the land.

"When I arrived in 2003, I was a true believer," said a former US marine. "I voted for Bush, I believed in the cause. Then I stayed for three years. "We were lied to. We went there for nothing and we came away with nothing. It cost a trillion dollars for this?"

"Put simply, the army didn't think Mosul was worth dying for," said Iyad Allawi, Iraq's first leader after Saddam Hussein and a leading political figure since then.

The price of their desertion is immense. Iraqi officials said on Friday that the jihadists had driven off with 200 armed trucks and humvess, supplied by the US. Most had been taken to Syria. They had torched the vehicles that they didn't have the manpower to deal with. An early bill for the losses is at least $1.2bn. A further $500m has been looted from banks and insurgent ranks have been swelled by at least 2,000 prisoners freed from local prisons.

By week's end Baghdad, a city so used to siege, had settled into a familiar rhythm. Shops were almost all closed, the few restaurants that opened were largely empty and the baking hot streets were deserted.

"It was like this before 2003," said a shopkeeper in the central city. It was like that three years later as well. But this might be the worst of all times.

As night fell, the back to the future theme continued. The few locals spending the early evening in tea shops tuned into another US president preparing to send bombers to Iraq.

Unlike George W Bush, though, Obama seemed a reluctant commander in chief.

Condemning the Iraqi army for its failure to "stand and fight", he said: "There's a problem with morale and commitment and ultimately that is rooted in the political problems that have plagued the country for a long time."

"In in the past decade American forces and taxpayers have made extraordinary sacrifices to give Iraqis a better choice and future. Unfortunately that hasn't been met by the same commitment from Iraq's leaders who can't seem to get past their sectarian differences."

Barely lifting his head, one local man, Abu Yousif said: "I completely agree with everything he said. Now lets get on with it."

No comments:

Post a Comment