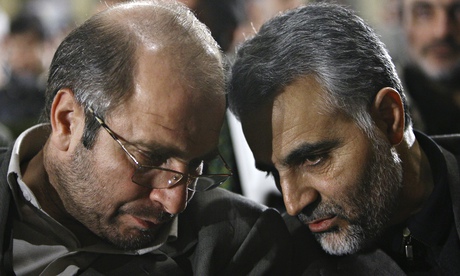

Qassim Suleimani, right, talks with Tehran's mayor Mohammad Bagher Qalibaf in 2006. Photograph: Mehdi Ghasemi/AP

Qassem Suleimani, commander of the Quds force of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), is a useful man to have on your side in a crisis. Nouri al-Maliki, Iraq's prime minister, must have been relieved to see him last week as he scrambled to organise a counterattack against the Sunni jihadis of Isis who have taken swaths of territory and were threatening Baghdad.

Suleimani is a regular, though usually unannounced, visitor to the Iraqi capital, where he has been a key player since even before the 2003 US invasion and the overthrow of Saddam Hussein. Stiffening resistance, mobilising militias and greasing palms is the stuff of a clandestine career which has given him the reputation of being one of the most powerful and mysterious men in the Middle East.

Now his latest mission to Baghdad is being seen as an indication of the gravity of the Iraqi crisis – a client of Tehran facing extremist jihadis. "The IRGC will see this as another front, akin to what is happening in Syria," said Ali Ansari, a historian of Iran at the University of St Andrews. "They are taking it very seriously indeed."

In the past three years, Suleimani, as the point man in Iran's strategic backing for Bashar al-Assad and its ties to Hezbollah, the Lebanese Shia movement, has focused on Damascus.

US sanctions imposed on him because of his role in Syria mean he is unlikely to meet any American officials – even if Washington and Tehran were to agree on short-term military cooperation in Iraq. Still, Suleimani was discreetly involved in negotiations with the US after the September 11 attacks, when Iran offered help to US forces in Afghanistan – until George W Bush included Tehran in "the axis of evil". Nowadays Iran's battle lines are clear. "Syria is the main bone of contention," Suleimani said in a rare speech in February. "On one side stands the whole world and on the other stands Iran. Some people urge Assad to go … but they don't realise the truth." Saudi Arabia, Tehran's bitter strategic rival and patron of some of the Sunni militants fighting Assad, came in for especially harsh censure.

Fiercely loyal to Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran's supreme leader, Suleimani usually keeps a low profile at home, his pale, almost ghost-like face, deep-set eyes and greying hair on show only occasionally at the funerals of IRGC men killed in Syria. Khamenei once branded him "a living martyr" – high praise. Last month a photo on Facebook showed him offering condolences to the family of Hilal al-Assad, the Syrian president's cousin, who was killed fighting near the Turkish border.

Suleimani, now 57, was in his early 20s when he joined Iran's forces in the war Saddam launched against the country in 1980 – a conflict that became the longest conventional war of the last century and which left more than a million dead on both sides in its eight bloody years. Afterwards he was deployed to Iran's eastern border, fighting drug smugglers from Afghanistan. In 1998, he was appointed commander of the Quds (Jerusalem) force.

Estimated to be several thousand strong, the Quds force carries out a range of highly sensitive functions: intelligence, special operations, arms smuggling and political action – anything that constitutes protecting the revolution or attacking its enemies, Israel foremost among them. "It combines the functions of MI6, the SAS and DfID," a British official quipped. "It is Iran's long arm – everywhere."

Suleimani was also pictured last year with the son of Imad Mughniyeh, the Hezbollah military commander whose assassination in Damascus in 2008 was widely blamed on Israel's Mossad secret service.

Experts agree that is hard to overestimate Suleimani's role in Iraq. "At times of crisis Suleimani is the supreme puppeteer," said Prof Toby Dodge of the London School of Economics. "He is almost like a Scarlet Pimpernel. He is everywhere and he's nowhere. He can be blamed for everything. Suleimani is doing in Baghdad what he did in Damascus – giving advice and help to an ally in trouble, Maliki in this case."

The Iranian's brash behaviour sometimes raises eyebrows: when he met the Iraqi president, Jalal Talabani, in 2008, according to one well-placed source, it looked like a "master-client relationship".

The previous year, during a series of battles between the US and Iraqi army on one side and Shia militias on the other, he sent an SMS message to the US commander, General David Petraeus. It read: "General Petraeus, you should know that I, Qassem Suleimani, control policy for Iran with respect to Iraq, Lebanon, Gaza, and Afghanistan. The ambassador in Baghdad is a Quds force member. The individual who's going to replace him is a Quds force member."

According to Dodge, one of Suleimani's most valued Iraqi assets is the Asaib Ahl al-Haq (the League of the Righteous), a Shia militia created by the Iranians to undermine the movement led by Muqtada al-Sadr, the Shia nationalist who emerged at the forefront of opposition to the US. Its leader, Qais al-Khazali, was one of the Iraqis Suleimani reportedly saw in Baghdad. "Like other Iranian-created structures, Asaib al-Haq is deeply religious and ideological and runs in parallel to the state, undermining it when it needs to and working with it when it doesn't," said Dodge.

The League of the Righteous staged some spectacular attacks against US troops before their withdrawal in 2011. Another old Iranian-backed Iraqi player, the Badr brigade, which was supposed to have been disbanded, reappeared in public last week.

Suleimani's public comments demonstrate a powerful sense of strategic commitment to Iraq and the preservation of both Iranian and Shia political power. "Iraq used to be the citadel of opposition against Iran," he said. "This is why they [the west] gave all that money to Saddam for such a long time, even before the creation of the Islamic republic."

No comments:

Post a Comment